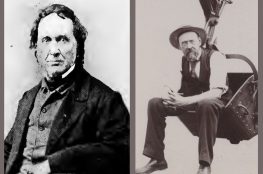

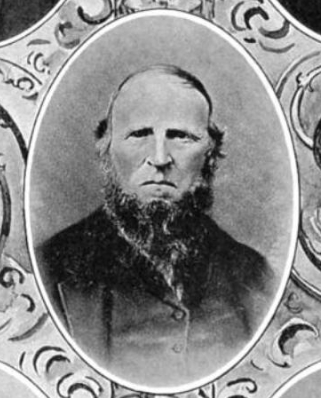

Peter Paddleford and his son, Philip Henry, left an indelible impact on covered bridge building in New England, particularly in New Hampshire.

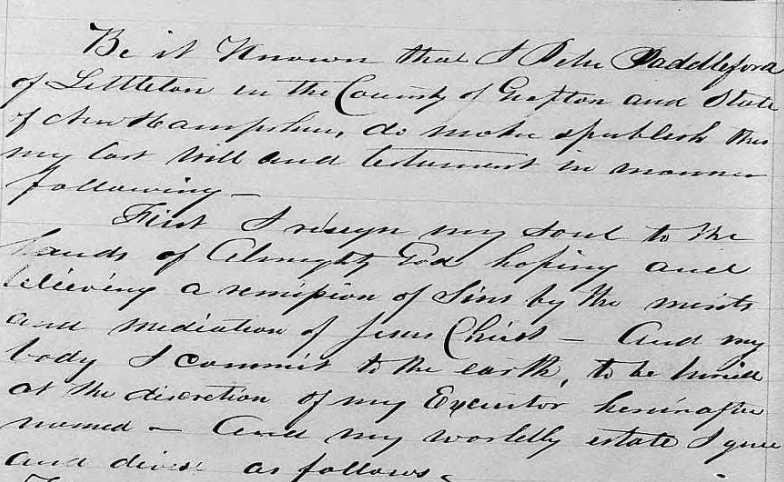

Peter H. Paddleford was born in 1785 in the Upper Valley town of Enfield, New Hampshire, about fifteen miles from the Connecticut River. Peter was the fourth of ten children born to Captain Philip Paddleford (1755-1832) and Ruth Bullock (1758-1847).

Peter’s father, Phillip, was a patriot of the Revolutionary War. Philip enlisted as a private in the 13th New Hampshire Militia Regiment during the American Revolution. Following his return from the successful Fort Ticonderoga campaign, his new hometown of Lyman gave him the honorary title of Captain, a title he carried throughout his lifetime.

On May 19, 1814, Peter married Dolly Sherburne (1785-1849) in Conway, New Hampshire. Dolly was born in the seacoast town of Portsmouth. It is unclear how the couple met one another, but they were both 29 years old at the time of their marriage.

The couple moved to Lancaster and had five children, Philip Henry (1815-1876), Sarah Sherburne (1816-1837), Phebe (b. 1824), Julia (1825-1860), and George Kennard (1829-1897). By 1840, the family had moved to Littleton, where Peter would reside until his death.

Peter supported his family with work as a millwright. He owned both a shop and a mill in Littleton. In 1815, he was one of many who signed a petition for a new covered bridge across the Ammonoosuc River in Bath. The following year, he was issued a patent for a device used in spinning wool and cotton. It is unclear if this device was ever made.

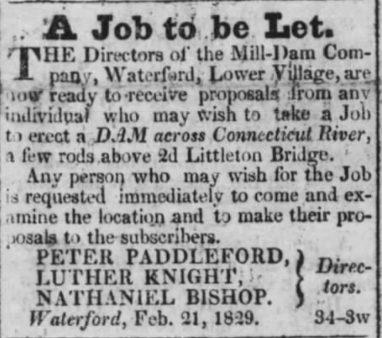

In 1829, Peter’s name appeared alongside that of Luther Knight and Nathaniel Bishop as a director of a Mill-Dam Company in Waterford, Vermont. An ad in the St. Johnsbury, Vermont Farmer’s Herald states the directors are “ready to receive proposals from any individual who may wish to take a job to erect a DAM across Contoocook River, a few rods above 2d Littleton Bridge” (Farmer’s Herald, 1829).

In 1837, Peter was appointed postmaster of North Lyman and held that post for several years. In 1842, Paddleford was named as a co-defendant along with Cyrus Eastman in a lawsuit over the purchase of property in Littleton. The case, in which George Little sued the defendants over a failed property sale, went all the way to the New Hampshire Supreme Court. Because Little’s property was encumbered, the court ruled in favor of the defendants.

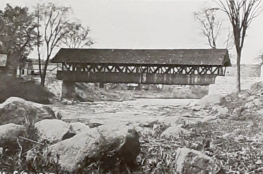

Peter’s bridge-building career seemingly began in 1834 with the construction of the McIndoe Falls/Lyman Bridge that connected Monroe, New Hampshire, to Barnet, Vermont. This 250’ bridge across the Connecticut River employed a Long truss.

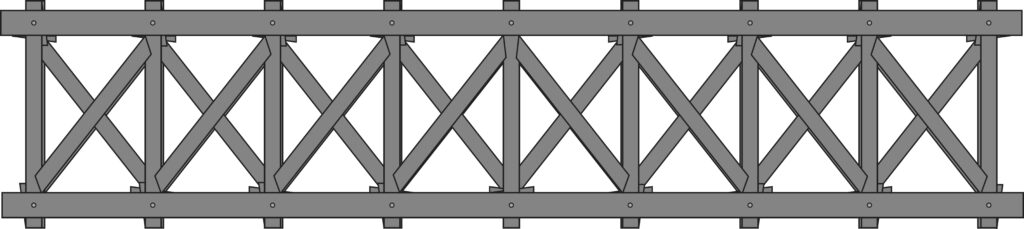

Designed by West Hopkinton native Colonel Stephen Harriman Long (1784–1864) in 1830, the Long truss is a series of timber braces arranged in an X pattern between a series of vertical posts. Long’s patent included the use of timber wedges where the chords, diagonals, and posts intersected. These wedges allowed the truss to be prestressed, minimizing the flexing of the truss when loads passed along them.

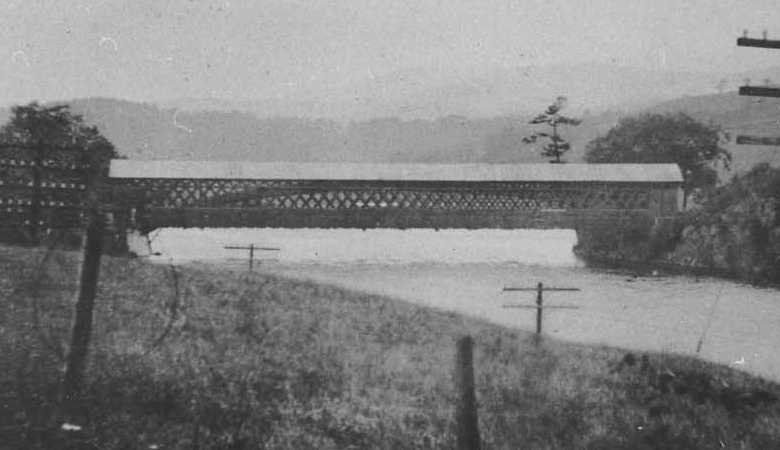

Peter used the Long truss again in 1842 with the construction of the Guildhall Bridge that connected Northumberland, New Hampshire, with Guildhall, Vermont. However, within a few years of building the Guildhall Bridge, Peter had seemingly tired of the Long truss and began to implement his own truss design. The 1846 Smith-Eastman or Joel’s Bridge in Conway is often attributed to being the first covered bridge designed by Peter. However, he is reported to have constructed Weston’s Bridge just across the New Hampshire border in Fryeburg, Maine, in 1844, which also used this unique design.

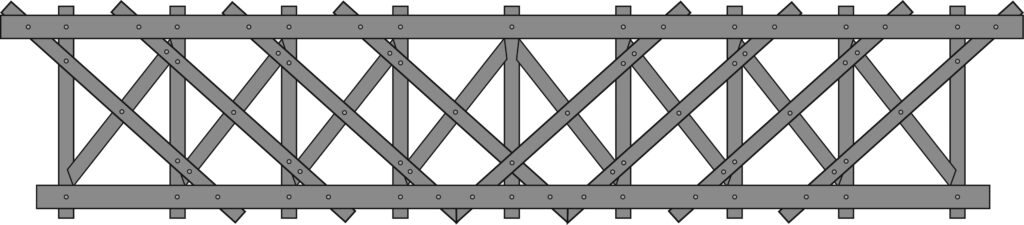

Either way, Peter had developed his truss design that, while never patented, became known as the Paddleford truss. The lack of a patent did not stop bridge builders from using the design; in fact, it may have encouraged it. According to historian Lola Bennett, the Paddleford truss dominated covered bridge building in northern New England for half a century.

It is often reported that the Paddleford truss is a modification of the Long truss and that Paddleford could not receive a patent because the owners of the Long truss challenged him in court. Documented evidence of this challenge is elusive. In fact, the resemblance between the two truss designs is somewhat disputed in the bridge community. According to bridgewright Will Truax, “this notion that a Paddleford is a modified Long holds no water, and has long done a disservice to the man and his Truss, and has caused many to somehow overlook the greatest aspects and the simple genius of his Truss.”

The two truss designs are similar in that the vertical posts are notched into the chords. But in the Paddleford truss, “channels are cut into the inner chord planks… where the counterbraces cross” (Nelson, 1997). The result is complicated joinery, according to bridgewright Jan Lewandoski. “Long designed his truss to implement his pre-stressing idea while Paddleford tried to make the braces work both in compression and tension by having the braces lap over all of the frame members. He tried to use wood like people later used iron rods. It’s hard to make a tension joint with wood unless you have a lot of distance to do it in” (Nelson, 1997).

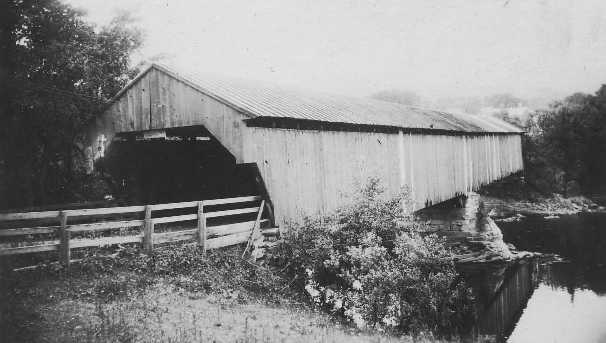

Peter Paddleford would build only four more covered bridges before he retired in 1849 at age sixty-four, including two more in Fryeburg and two in his native New Hampshire. Despite announcing his retirement a year earlier, in 1850, he built the Saco River Bridge alongside Jacob E. Berry (1802-1870), an esteemed bridge builder in his own right who would go on to almost exclusively use the Paddleford truss. The Saco River Bridge was destroyed in the 1869 freshet when the raging Swift River tore its namesake bridge off the abutments and hurled it into the Saco River Bridge, destroying them both.

Sadly, none of Peter’s covered bridges remain.

1834. McIndoe Falls/Lyman Bridge. Monroe, New Hampshire, and Barnet, Vermont. Lost 1930.

1842. Guildhall Bridge. Northumberland, New Hampshire, and Guildhall, Vermont. Lost 1853.

1844. Weston’s Bridge. Fryeburg, Maine. Lost 1947.

1846. Smith-Eastman/Joel’s Bridge. Conway. Lost 1975.

1846. Canal Bridge. Fryeburg, Maine. Lost 1929.

1848. Walker’s Hill Bridge. Fryeburg, Maine. Lost 1931.

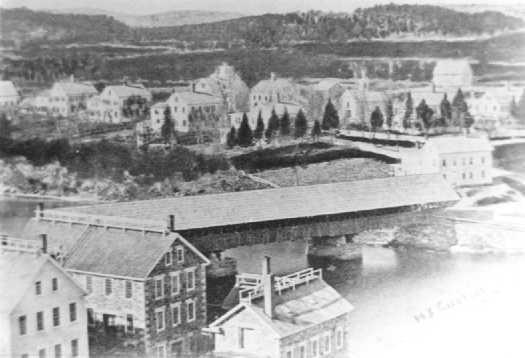

1848. Main Street Bridge. Penacook. Lost 1874.

1850. Saco River Bridge. Conway. Lost 1869. Built with Jacob Berry.

Peter’s suspected retirement year coincides with the death of his wife of thirty-six years. Dolly died on December 5, 1849. Peter would die ten years later on October 18, 1859, at age seventy-four.

As for their children, Sarah Paddleford died in 1837 at age 21. Phebe Paddleford married Salmon G. Miner and resided in Gilford. In 1850, daughter Julia married Harmon Marcy (1819-1894), who built the original Smith Bridge in Plymouth that same year. Marcy’s bridge-building partner was Julia’s brother, Philip Henry. The young couple lived in the Paddleford home before moving to Shelbyville, Illinois, where Julia would die in 1860. Their youngest son, George Kennard Paddleford, operated a Littleton pharmacy and served as an officer in the Fourth Division New Hampshire Militia. He died of pneumonia at age sixty-five.

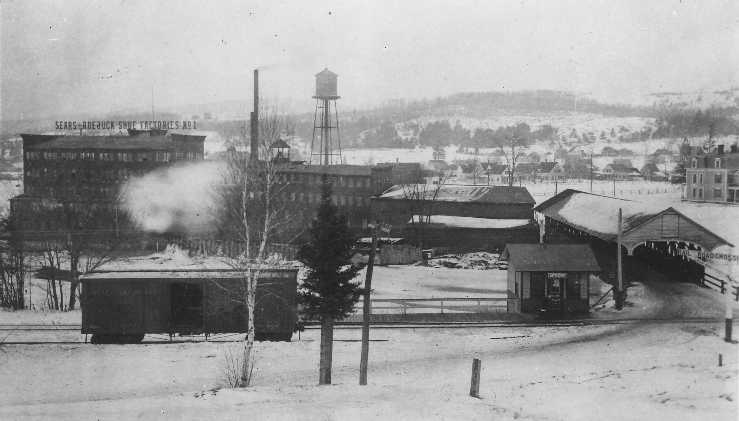

The eldest son, Philip Henry (who seemingly went by Henry), worked alongside his father beginning in at least 1835 and took over both the shop and the bridge building business after his father retired. Henry would go on to construct at least five covered bridges in New Hampshire, including the 1850 Federal and Bridge Street bridges and the 1853 Sewall’s Falls Bridge in Concord; the 1852 Apthorp Bridge in Littleton; and the 1877 Beards Falls/Stevens Village Bridge across the Connecticut River in Monroe.

Of the covered bridges Philip Henry is reported to have constructed, none remain.

1850. Federal Bridge. Concord. Lost 1872.

1850. Bridge Street/Free Bridge. Concord. Lost 1894.

1852. Apthorp Bridge. Littleton. Lost 1927.

1853. Sewall’s Falls Bridge. Concord. Lost 1862.

1877. Beards Falls/Stevens Village Bridge. Monroe, New Hampshire, and Barnet, Vermont. Lost 1938.

Henry also constructed several buildings in Littleton, including his brother’s pharmacy. He expanded the family sawmill to include a woodworking and machine shop; with his partners, Henry built and repaired all the sawmills, gristmills, and factories in the Ammonoosuc Valley. He was known as a “reliable man, intelligent and well-read in matters beyond the scope of his business, retiring, but eager to help others both in private and public matters” (Jackson and Furber, 1905).

Henry dabbled in politics, having been elected to the legislature in 1855. “He was generally held in such high esteem that he was often nominated by his party friends for public office for the purpose of strengthening it when defeat was inevitable but a full vote desired” (Jackson and Furber, 1905). Henry died in 1876 at age sixty-one.

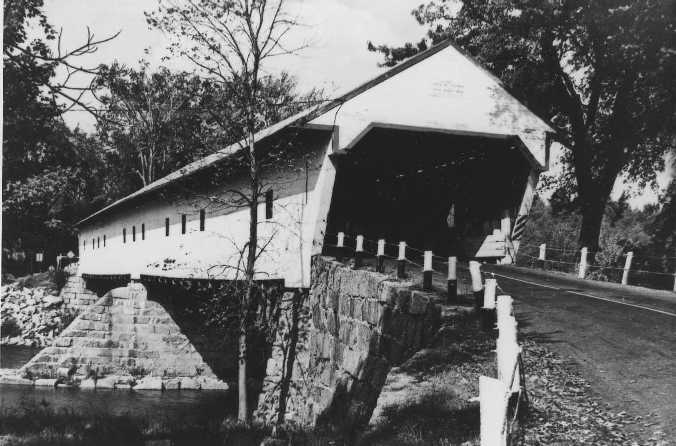

Bridgewrights such as the aforementioned Berry and his son, Jacob H. Berry (1827-1892), and Charles A. Broughton (1835-1909) of Conway implemented the Paddleford truss in their covered bridges. It is estimated that there were at least fifty-one Paddleford truss bridges in New Hampshire, forty-nine in Maine, and thirty-four in Vermont.

Of that estimated 134 bridges, only twenty-two Paddleford truss covered bridges remain in the world. Five—Lovejoy, Hemlock, Bennett-Bean, Sunday River, and Porter-Parsonfield bridges—are in Maine; three—Sanborn, Lord’s Creek, and Coventry—are in Vermont; and fourteen are in New Hampshire: Jackson, Bartlett, Saco River, Swift River, Albany, Durgin, Whittier, Happy Corner, Pittsburg-Clarksville, Groveton, Stark, Mechanic Street, Swiftwater, and Flume.

References

Historical photos used with permission from Covered Spans of Yesteryear and the National Society for the Preservation of Covered Bridges.

Bennett, Lola. 2004. Historic American Engineering Record, Mechanic Street Bridge, HAER No. NH-45. Washington, D.C.: National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior.

Christianson, Justine, and Christopher H. Marston. 2015. “The Preservation and Future of Covered Bridges in the United States.” In Covered Bridges and the Birth of American Engineering, by Justine Christianson and Christopher H. Marston, 185–203. Washington, D.C.: Historic American Engineering Record, National Park Service.

Farmer’s Herald. 1829. “A Job to be Let.” Farmer’s Herald, February 24, 1829.

Jackson, James Robert, and George Clarence Furber. 1905. History of Littleton, New Hampshire: Topical history. Cambridge, MA: University Press.

Nelson, Joseph C. 1997. Vermont Bridges. April 9. Accessed September 11, 2022. http://www.vermontbridges.com/paddle.htm

Reports of Cases in the Superior Court of Judicature of New Hampshire, Volume XIII. 1847. Concord, NH: Asa McFarland Publisher.

Truax, Will. 2015. The Bridgewright Blog. January 31. Accessed September 11, 2022. https://bridgewright.wordpress.com/category/paddleford-truss/.