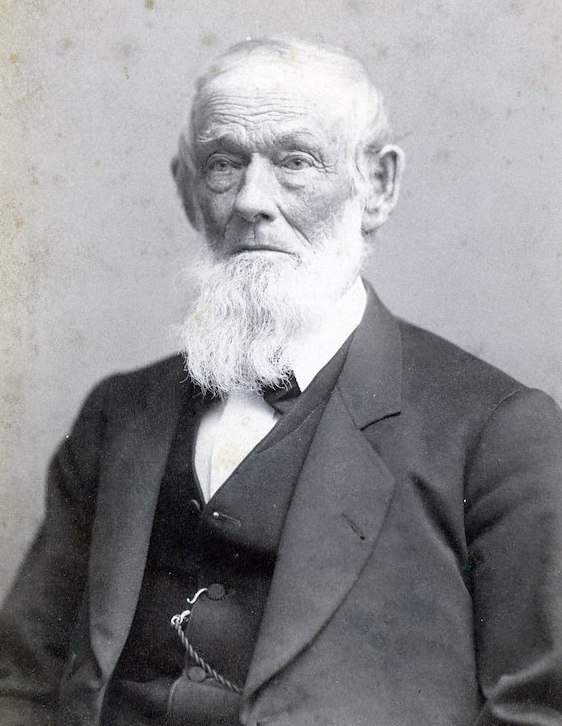

Bridgewright Horace Childs comes from a long line of Puritan Yankee stock. His fourth great-grandfather, William, was one of the earliest settlers of the New World. William arrived from England in 1630 and settled with his family in Watertown, Massachusetts. The family would remain there until Horace’s grandfather, Solomon Childs (1743-1827), and his wife, Martha Rice (1746-1804), moved to Henniker shortly after their marriage in 1767, where they established a farm.

Horace was born on August 10, 1807, the first of eleven children born to Solomon Childs, Jr. (1781-1865) and Mary “Polly” Long (1784-1823). In addition to maintaining the family farm in Henniker, his father was a carpenter and cabinetmaker. For several years, he was employed in building factories in Dover, fifty miles east of Henniker. It appears Solomon traveled back and forth for this employment as his family remained in Henniker.

Horace spent his childhood on the farm with his parents and surviving siblings. Only seven of the Childs children would live into adulthood. Three of his siblings, David C. (1815-1816), William C. (1816), and Celestia M. (1818-1820) died as infants. Brother David Curtis (1818-1837) died of an ulcerating stomach at age twenty.

When Horace was sixteen years old, his mother Polly died eighteen days after giving birth to her last child, Caroline (1823-1867). No cause of death is listed on her death certificate, but it is plausible that the 39-year-old may have died after suffering complications from childbirth.

That same year, 1823, Horace left the farm and went to work with his father, building factories on the seacoast. At some point, Solomon sent Horace back to Henniker to finish his education. A story recounted in a biographical review indicates Horace’s inclination to save a dollar. “While working in the latter place, his father decided to send him home to attend school, and fitting him out with clothing gave him a dollar to pay his stage fare. Young Horace, however, decided to walk, and seems to have kept on traveling afoot until he reached Hopkinton” (Biographical Review 1897).

Once he arrived home, it seemed Horace did not take his father’s advice to go back to school. Instead, he moved north to Claremont, where he worked as a carpenter. While in Claremont, he became quite ill with typhoid fever. His younger sister, Mary (1810-1896), left school to care for Horace. As he recovered, he decided to go back to school after all. Horace attended Hopkinton Academy, working as a carpenter to pay his way.

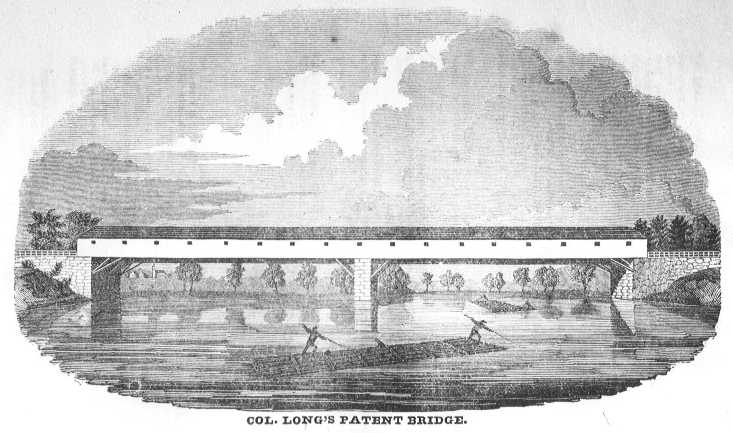

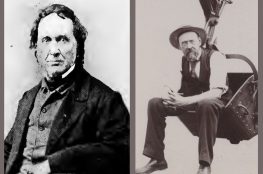

It was during this time that Childs connected with his first cousin, once removed, Colonel Stephen Harriman Long (1784-1864). Long was an army civil engineer, explorer, and inventor born in Hopkinton to Moses Long (1760-1848) and Lucy Harriman (1784-1837). Horace’s maternal grandfather and Long’s father were brothers. In addition to many military expeditions, Long consulted with various railroads and eventually patented his truss design for wooden covered bridges in 1830 and 1839.

In the early 1830s, Long moved his family back to Hopkinton, and Horace boarded with his cousin for a short time, using his carpentry skills to earn his keep. Horace was mainly focused on residential building and employed other local carpenters, including Frederick Whitney (1806-1879), Dutton Woods (1809-1884), and Thomas Livingston (1800-1878).

As the story goes, Long was so impressed with Horace’s work that he offered him the lead on a contract for a covered bridge in Haverhill. Horace constructed the New Bridge over the Connecticut River, connecting Haverhill, New Hampshire, to Newbury, Vermont, in 1834. The New Bridge was the first covered bridge in New Hampshire to be built using Long’s truss design and marked the beginning of Horace’s career as a bridge builder. He was twenty-seven years old.

In 1835, Horace built a home for himself on Maple Street in Henniker. The following year, the Town of Henniker was looking for a location for a new school. Horace donated land adjacent to his property for the project and was contracted by the town to build the Henniker Academy. On January 3, 1837, Horace married Matilda Rowena Taylor (1816-1897) of Lempster. The couple had no children.

Following his success with the New Bridge, Horace was awarded several covered bridge contracts of his own, including two in his hometown. Horace built the “first bridge of the kind in this town, across the river at West Henniker, in 1835” (Cogswell 1880). Known as the Amsden Mill or Upper Bridge, this structure was destroyed when ice knocked down one of the piers in May 1852. A replacement bridge was built by Horace’s former employee, Frederick Whitney, and stood until it was replaced in 1915. No photos of Horace’s bridge exist.

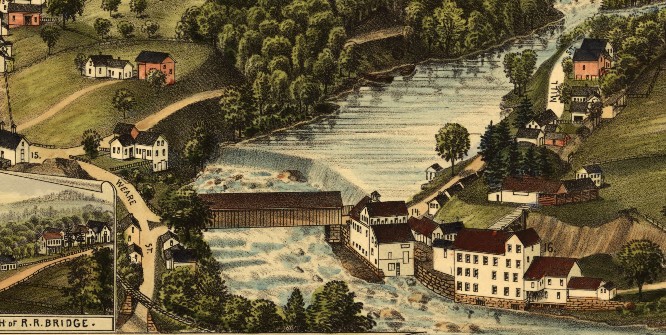

In 1843, Horace constructed the Lower or Howes Mill Bridge in Henniker. This structure stood on what is now Ramsdell Road until it was destroyed by fire in 1900. There are no photos of this bridge, but it is illustrated on an 1889 map of Henniker drawn and published by George E. Norris of Burleigh Litho.

The demand for Horace’s bridge-building services grew as the railroad lines spread throughout the country. “With Long’s assistance and prestige, Childs was able to obtain many contracts for covered railroad bridges, and as the railroad’s demands were urgent, they were willing to pay premium prices for the means of crossing the streams of their right of way” (Walker 1959).

In 1839, Horace landed a contract with the Hartford and New Haven Railway Company. Despite paying Long a royalty for using his patent, Horace greatly profited from his work building covered bridges along the railroad line. His first bridge on this line was the 1839 Hartford & New Haven Railroad bridge in Hartford, “a heavy bridge of one span carrying three tracks, and the depot was built partly on the bridge. Most of the timber for the bridge … was cut in Haverhill, NH, and run down the river to Olcutt’s Falls below Hanover. There it was sawed and then rafted down the river through several sets of locks to Hartford” (Daily Morning Journal and Courier 1899).

In 1837, Whitney and Woods left Horace’s employ to pursue their own bridge work. By 1846, Horace’s business had grown so significantly that he hired his two brothers to come work with him. Enoch (1808-1881) came on as the civil engineer and business manager, and Warren (1811-1898) as the mason at what was now known as H. Childs & Co.

Enoch Long Childs was educated at Hopkinton Academy. In 1831, he entered Yale College and completed one year before withdrawing and returning to Hopkinton to teach at the Academy. He returned to Yale in 1837 and graduated with a civil engineering degree in 1840, the same year he married Harriet “Hattie” Long (1816-1881). Enoch opened Montgomery Academy in Alabama the following year, where he served as principal for six years before returning to New Hampshire in 1846. Enoch is listed in census records as a railroad conductor, civil engineer, and gentleman. He and Hattie had no children.

Warren Story Childs attended Yale for one year before returning to the family farm with his father. He married Sarah Tilton Lane (1815-1890) of Candia in 1830. The couple had four children: Richard Lane (1843-1909), Curtis Benson (1845-1923), Mary Abby (1849-1912), and Frederic Warren (1853-1854). Census records list Warren’s occupation as a farmer.

Reports in various histories indicate that the Childs brothers constructed bridges on the Providence & Worcester Railroad, the Northern Railroad from Andover to White River Junction, and the New Hampshire Central Railroad. They also had contracts on railroad lines in Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New York.

A Yale College fraternity catalog specifies that Enoch worked as the “architect of bridges for the Providence & Worcester, the Norfolk County, the Northern New Hampshire, and the Passumpsic Railroads, and contractor with his brothers for the Concord & Bristol, and the New Hampshire Central Railroads” from 1846-1853, the Somerset & Kennebec Railroad from 1853-1856, and the Troy and Greenfield (Hoosac Tunnel) Railroad from 1860-1862 (Yale, 1888).

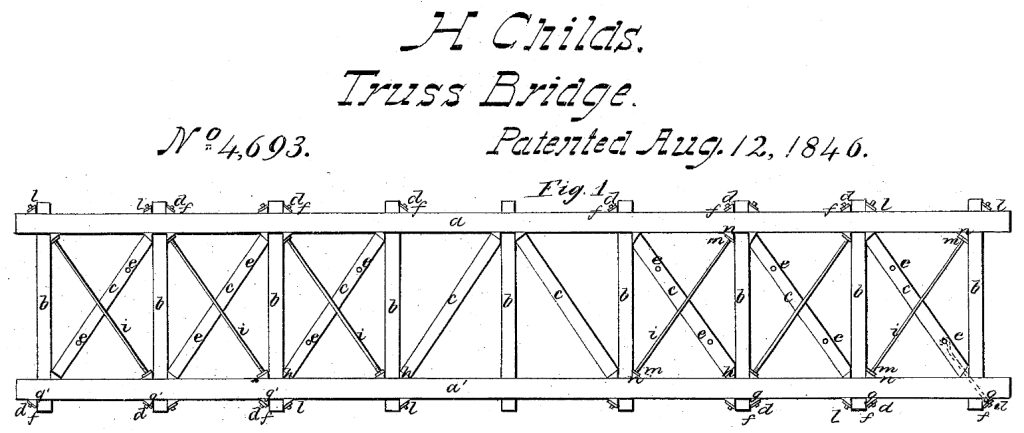

The Childs implemented several types of trusses in their covered bridges, including Long, Pratt, Town lattice, and Burns’ truss designs before Horace patented his own truss design in 1846.

In 1851, H. Childs & Co. was hired by the City of Manchester to build a railroad bridge across the Merrimack River in the heart of the city. Named the Granite Street or Merrill’s Bridge, the structure was a four-span bridge of an undetermined length. Horace was injured during the construction of the bridge, badly breaking his leg. The injury would have a significant impact on his business. “This accident so interfered with his work that he decided to refrain from taking large contracts in the future, and from that time until his retirement, he devoted his attention to work nearer home” (Biographical Review 1897). Before the injury, Horace had contracted to build railroad bridges in Maine; his brothers fulfilled the contracts.

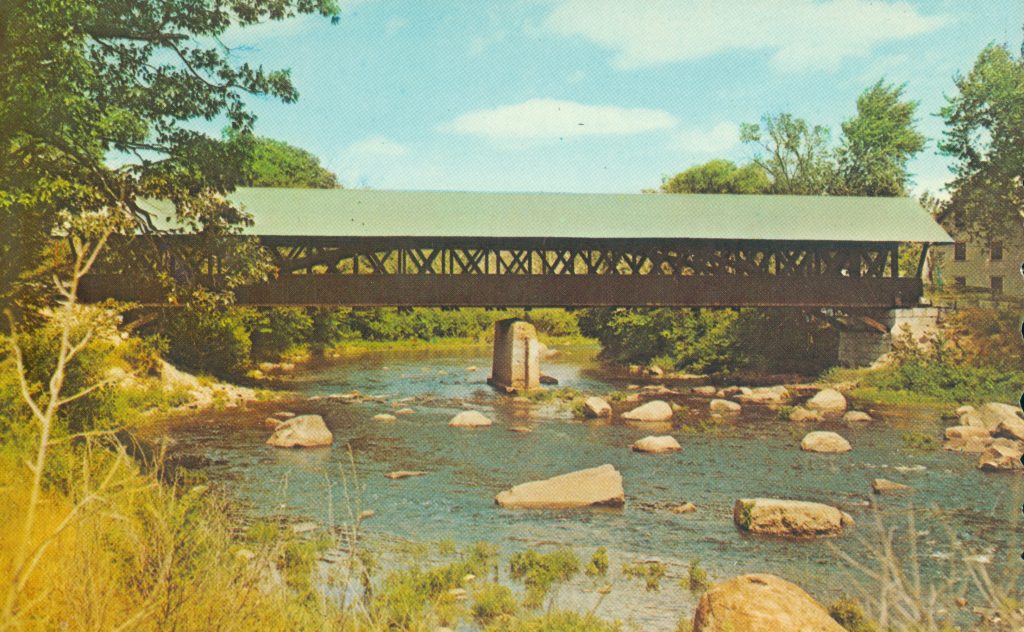

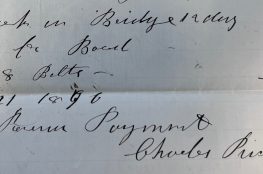

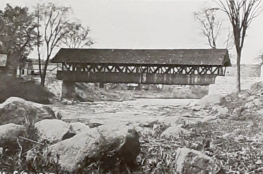

In 1853, Horace would build his last covered bridge in the neighboring town of Hopkinton. When the West Hopkinton or Rowell Bridge was destroyed in a flood in 1852, the town of Hopkinton contracted with H. Childs & Co. to replace it and paid $2,637.64 for the work. Oddly enough, the Rowell Bridge does not employ either a Childs or a Long truss. Horace constructed the bridge using a unique truss design that had never been seen before or since. “One might suspect that it is a unique one-of-a-kind masterpiece where Childs used most everything he had learned to put together the strongest and best bridge he possibly could for his neighbors” (Sindelar 2020).

The covered bridges known to have been specifically constructed by the Childs Brothers are listed below. Ongoing research may uncover more.

1834. New Bridge. Haverhill, NH/Newbury, VT. Replaced in 1913. Built by Horace Childs.

1835. Amsden Mill/Upper Bridge. Henniker. Lost in May 1852 to ice. Built by Horace Childs.

1836. Hartford Village Bridge. Hartford, VT. Lost in 1892 by flood. Built by Horace Childs.

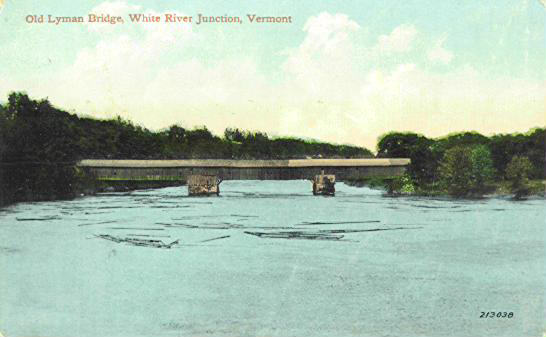

1837. Lyman’s Bridge. West Lebanon, NH/Hartford, VT. Replaced in 1895. Built by Horace Childs.

1837. Fox/Foxville Bridge. Royalton, VT. Lost in 1866. Built by Horace Childs.

1843. Lower/Howes Mill Bridge. Henniker. Lost in 1900 to fire. Built by Horace Childs.

1848. Connecticut & Passumpsic Rivers Railroad Bridge. White River Junction, VT. Replaced in 1890. Built by Henry R. Campbell & Horace Childs & Co.

1851. Merrill’s/Granite Street Bridge. Manchester. Lost between 1857-1862. Built by H. Childs & Co.

1853. Rowell Bridge. Hopkinton. Built by Horace Childs.

1853/1857. Canterbury Bridge. Boscawen/Canterbury. Lost in 1896 by flood. Built by Enoch L. Childs.

1855. North Fork Bridge. Skowhegan, ME. Lost 1903. Built by Enoch L. Childs.

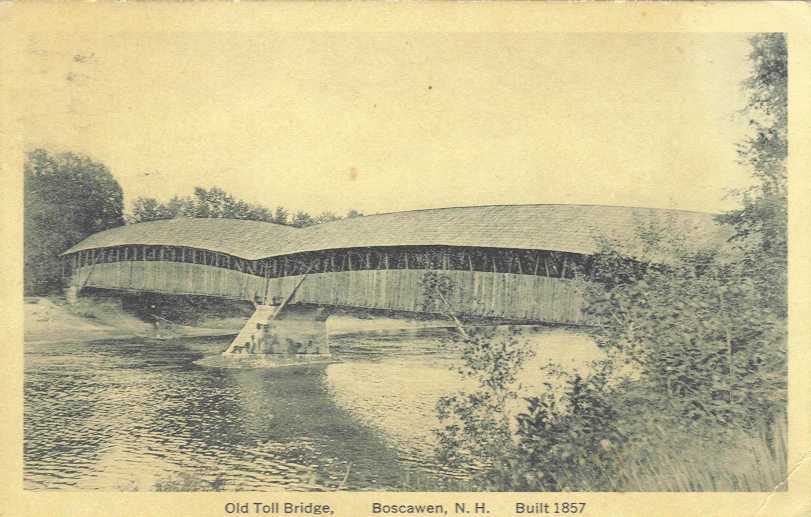

1857. Rainbow Bridge. Boscawen/Canterbury. Lost in 1907 by flood. Built by Enoch L. Childs.

The Rowell Bridge is the only surviving covered bridge built by Horace Childs.

Work on the Rowell Bridge began in 1852. Town reports indicate payments were made in 1852, and the account was settled in 1853. When the bridge was completed is unknown, but Horace’s work on the project ended in January 1853.

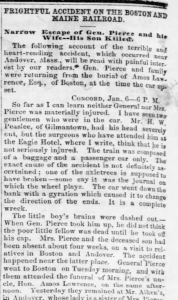

On the afternoon of January 6, 1853, Horace was one of sixty passengers on a Boston and Maine train heading to New Hampshire from Hartford, Connecticut. When the train stopped in Andover, Massachusetts, United States President-Elect and New Hampshire native Franklin Pierce, his wife, Jane, and their son, Benny, boarded the train. Two miles north of Andover, the forward axle of the passenger car broke. The damage sent the car off the track and tossed it down a steep 15-foot embankment. The train car was broken into fragments, and several passengers were seriously injured. Young Benny Pierce was struck in the head by a piece of the train car and instantly killed. He was eleven years old.

Horace suffered significant injuries in the crash. One report indicates that Horace was “picked up for dead” (Biographical Review 1897), but an article in the New England Farmer states he experienced bruising of his head and face. After the accident, Horace retreated to his home in Henniker to recover from his injuries. He never returned to bridge building.

Warren Childs retired from bridge building the same year and focused his efforts on his Henniker dairy farm. Warren died on April 10, 1888, of typhoid fever at age 75.

Enoch Childs continued building bridges for the railroad and for other communities. He oversaw the construction of the Canterbury and Rainbow Bridges in Canterbury and Boscawen. In 1862, Enoch Childs changed careers and took a job with the Internal Revenue Service, where he began as a clerk and retired as a chief deputy collector in 1870. In March 1880, he suffered an injury to his spinal column that left him prostrate. Enoch died on September 8, 1881, of a fever at the age of 72. His wife, Hattie, had died just eighteen days earlier of epilepsy.

It is worth noting that several publications indicate that the three covered railroad bridges in Hooksett were constructed by the Childs brothers in 1868. But all three brothers had retired from bridge building by then. Extensive research has concluded that the triple bridges on the Suncook Loop were rebuilt in 1889 by the Concord Railroad, not the Childs.

Horace spent the rest of his life in his hometown of Henniker, where he was considered a generous and benevolent man. He was a long-time member of the Henniker Congregational Church and would later serve as Deacon. He and fellow parishioner Fayette Conner (1824-1889) paid for the repair of the building and purchased a church organ.

Horace valued both education and hard work. In addition to incorporating and building Henniker Academy, he financially supported several young men in obtaining their education. He was also a sober man. Horace was “an earnest advocate of temperance, making it a point, when employing men upon public works, that no ardent spirits should be used in or about the works” (Hurd 1885). He was a staunch Republican and a life member of the American Board of Foreign Missions.

Horace’s wife Matilda died in 1897 at age 80. After her death, Horace went to live with his nephew, Curtis Benson Childs. Curtis was educated at Henniker Academy and the Chandler Scientific Department at Dartmouth College. Curtis worked as a civil engineer and was engaged in surveying for railroad construction in Iowa, Kansas, Colorado, Missouri, the Indian Territory, and Texas before returning to New Hampshire in 1876 to operate the family farm.

Horace died on June 7, 1900, at the age of ninety-two. He is buried alongside his wife in the Henniker Cemetery.

Horace was remembered as “a man of strict integrity, marked generosity, and liberality of character. As a business man successful, as a citizen respected and beloved, and as one who has done much to further and promote the improvement and prosperity of his native town, he stands among her representative men, and is a worthy descendant of the ‘old pioneer’ “ (Hurd 1885).

Sadly, Childs’ truss design has been relegated to history. There are seven covered bridges in Ohio that employed a variant of his truss design. New Hampshire native Everett S. Sherman (1831-1897) constructed several bridges based on Child’s truss design in Ohio in the late nineteenth century. According to National Society for the Preservation of Covered Bridges co-vice president Scott Wagner, “It seems obvious that Sherman was inspired by Childs’ design, but he chose to make a few design modifications that differentiate his design from the intentions of Horace, as described in his patent description from 1846. No true examples of Horace’s truss design remain today” (Wagner 2024).

In New Hampshire, Childs’ craftsmanship can be seen in the Rowell Bridge, his home on Maple Street, and the adjacent Henniker Academy building. The Academy building is now home to the Henniker Historical Society, which houses other evidence of Horace Childs. His photograph is posted proudly at the entrance to the museum room. Inside, one can see Childs’ Long truss model with an engraved H. Childs & Co. business card tacked to the top. His legacy lives here, in the building he crafted almost two hundred years ago. He is not forgotten.

References

Historical photos were used with permission from the Henniker Historical Society, Covered Spans of Yesteryear , and the National Society for the Preservation of Covered Bridges.

Special thanks to Sue Fetzer, Marc McMurphy, Martha Taylor, Henniker Historical Society; Scott Wagner and Bill Caswell, National Society for the Preservation of Covered Bridges.

Biographical Review Publishing Company. 1897. Biographical Review; containing life sketches of leading citizens of Merrimack and Sullivan counties, N. H. Boston: Biographical Review Publishing Company.

Child, Elias. 1881. Genealogy of the Child, Childs, and Childe Families: Of the Past and Present in the United States and the Canadas, from 1630 to 1881. United States.

Childs, Horace. 1846. Truss Bridge. US Patent 4,693, issued August 12, 1846.

City of Manchester. 1847. Annual Report of the Committee on Finance on the Receipts and Expenditures of the City of Manchester, Together with the Treasurers’ Accounts. United States.

Cogswell, Leander Winslow. 1880. History of the Town of Henniker, Merrimack County, New Hampshire. Henniker, NH: Republican Press Association.

Collections of the Dover, N.H., Historical Society. 1894. United States: Scales & Quimby.

Daily Morning Journal and Courier. 1899. “First Railroad Bridge: Builder of Structure in Hartford Now Living.” Daily Morning Journal and Courier. November 18, 1899.

Granite Monthly: A New Hampshire Magazine. 1894. United States: Granite Monthly Company.

Hurd, D. Hamilton. 1885. History of Merrimack and Belknap Counties, New Hampshire. Philadelphia, PA: J. W. Lewis & Company.

Lord, Charles C. 1890. Life and times in Hopkinton, NH. Concord, NH: Republican Press.

New England Farmer. 1853. “Sad Railroad Accident.” New England Farmer. January 15, 1853.

Sindelar, James. 2020. “Hopkinton New Hampshire’s Rowell Bridge.” Covered Bridge Topics, Spring: 3-7.

Walker, C. Ernest. 1959. Covered Bridge Ramblings in New England. Contoocook, NH: C. Ernest Walker.

Yale College. 1888. General Catalogue of the Psi Upsilon Fraternity. United States.

February 10, 2024

Is this material available as a printed book?

February 10, 2024

Hi Mason,

Not as of yet!