Note: This post was updated in June 2024 with new information uncovered by Bill Caswell (June 2024).

Frederick Whitney was born in Henniker on October 5, 1806. He was the third of six children born to Eleazer Whitney (1777–1838) and Alice Peabody (1779–1867) and was the only one of his siblings to live to old age. Little is known about Whitney’s childhood apart from a significant tragedy in 1819 when he was just thirteen.

That June, his two younger brothers, Benjamin “Carroll,” age ten, and Alexander, age seven, died by drowning. The boys drowned in the Contoocook River about a half mile southeast of the village. They were buried with a combined tombstone in the Center Cemetery in Henniker. The circumstances of their death surely weighed heavily on the Whitney family.

It is unclear where Whitney was educated, but we do know he was trained as a carpenter. Eventually, he went to work for the Childs Brothers of Henniker. Led by elder brother Horace Childs (1807-1900), H. Childs & Co. was founded in 1834 and constructed many covered bridges along the New Hampshire railroad lines and lines in New York, Ohio, and Pennsylvania. Whitney began his tenure with the Childs as a simple carpenter. By the time he left their employ, he was a skilled bridgewright. It is unclear exactly when or for how long Whitney was employed by the Childs, but his work there proved to be advantageous for him both personally and professionally.

While at H. Childs & Co., Whitney worked alongside another young carpenter, Dutton Woods (1809-1884). Woods apprenticed with Childs from 1830 until 1837 before going out on his own. Soon after, Whitney would join him in business. In March 1837, the two purchased a parcel of land in Henniker for $150. The deed identifies the boundaries as “the northerly side of Mill Brook, thence northerly forty-five feet to a stone part to the road leading from Woods Mills.”

The two reportedly, “…built all the bridges upon the line of the Concord & Claremont and Contoocook Valley Railroads. They constructed bridges for many years when Mr. Whitney retired from the business” (Cogswell 1880). What specific railroad covered bridges Whitney and Dutton may have constructed have been lost to time. Regardless, none of those railroad bridges remain today.

Not only were the two business partners, but they soon became family. On January 22, 1835, Whitney married Dutton Woods’ younger sister, Fidelia. He was twenty-nine years old; she was twenty-four. On October 20, 1838, the couple welcomed a daughter, Julia F. Their second child, a son named Frederick, was born in July 1846. He died ten weeks later.

Woods would go on to build at least eight highway covered bridges in his lifetime. As far as we know, Whitney constructed two.

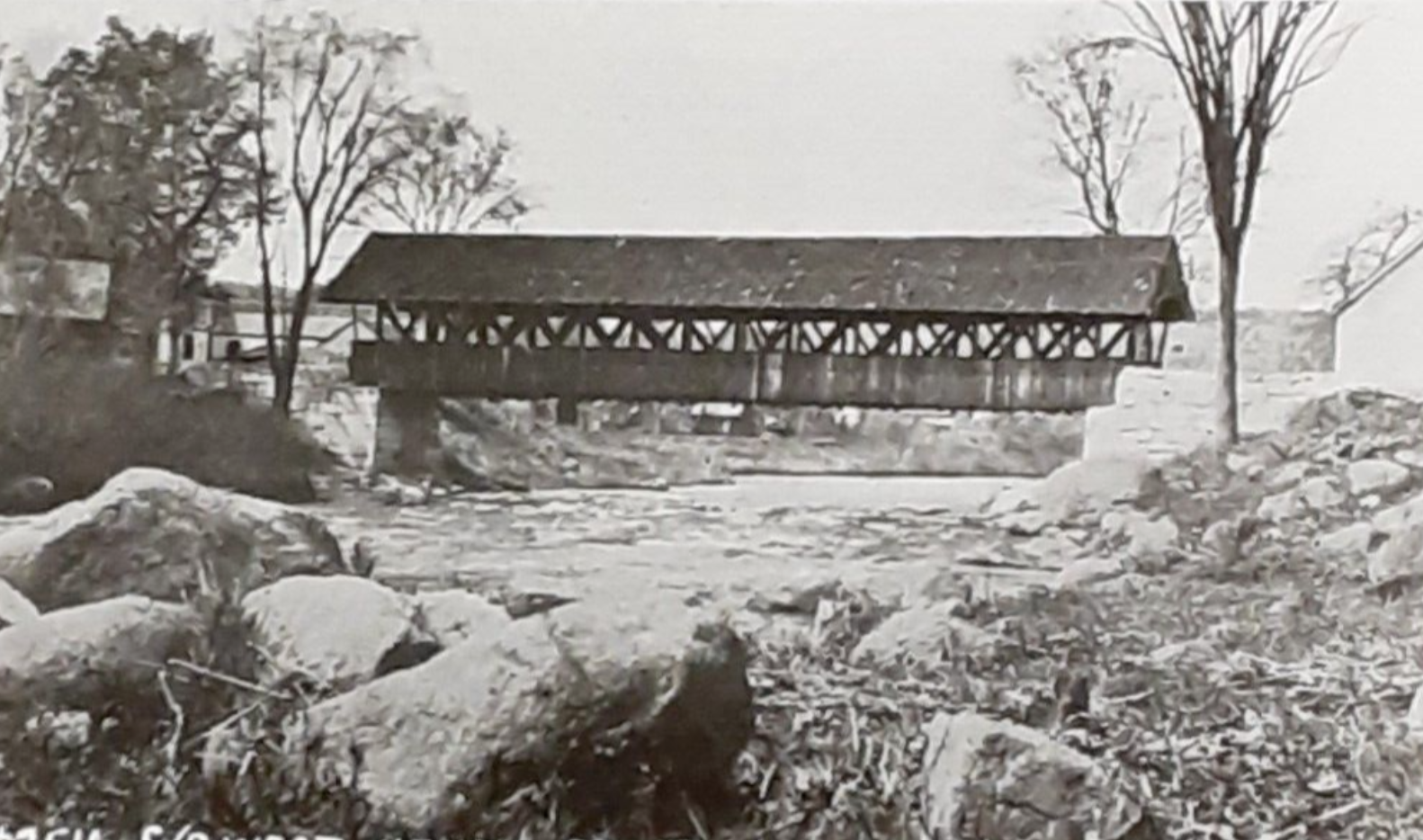

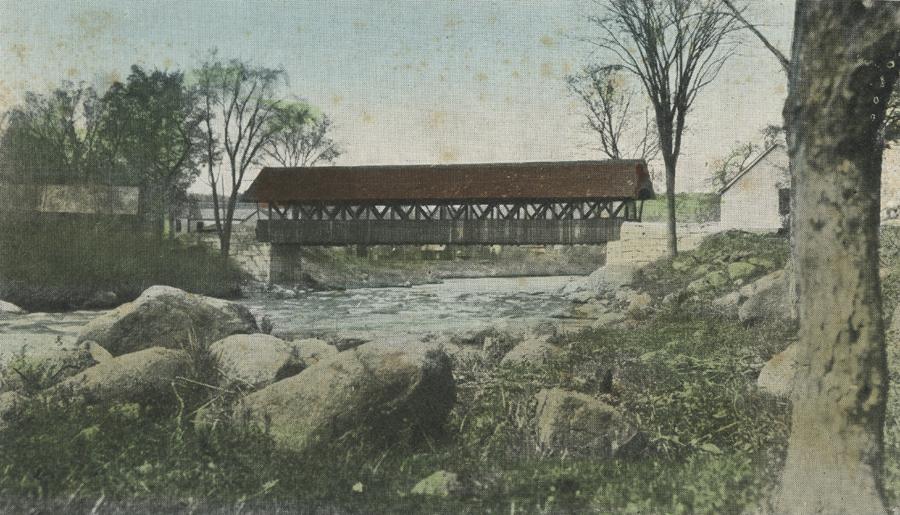

In 1844, Whitney built the Hillsborough-Henniker Road Bridge alongside Horace Childs. The bridge cost $1,097.66 to construct. The abutments were built by Daniel Reed for $420. The bridge was destroyed by fire on July 2, 1899. The photo below is believed to be the Hillsborough-Henniker Road Bridge.

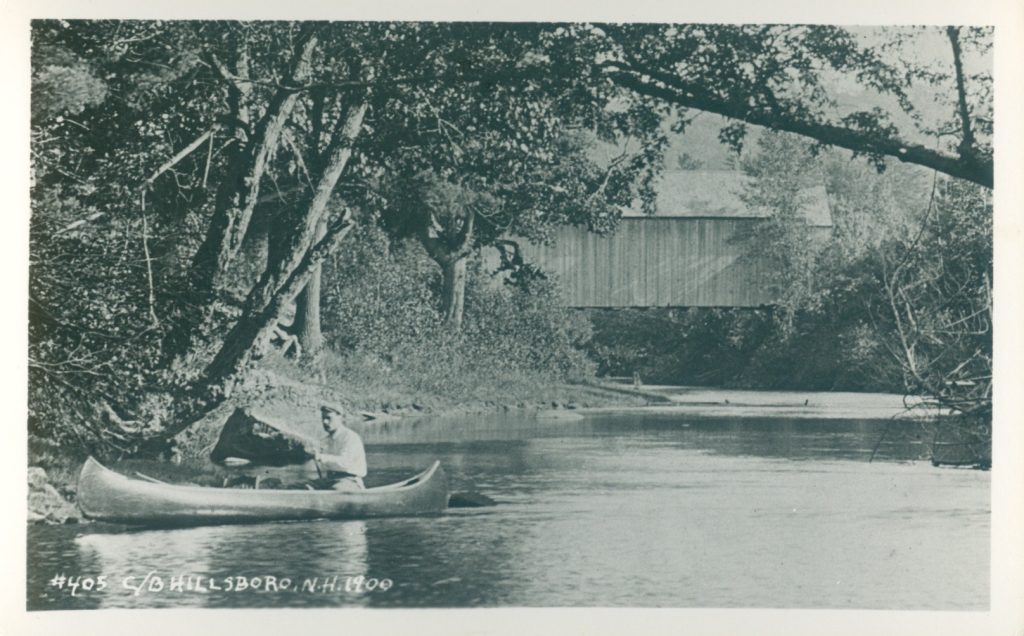

The Amsden Mill, or Upper Bridge, was constructed in West Henniker in 1834 by Horace Childs. The bridge was one of the first structures built by Childs and employed a Long Truss, designed by Childs’ cousin, Col. Stephen Harriman Long (1784-1864). Given that Childs employed Whitney at the time, it’s possible that he worked on the bridge during its construction. When this covered bridge was destroyed by an ice floe in May 1852, Whitney was contracted by the town of Henniker to replace it.

Whitney was paid $185 as “agent, in part to build upper bridge” (Town of Henniker 1853). He constructed a 110’ covered bridge over the Contoocook River; the truss design he employed seems to be up for debate. The bridge is described as both a Paddleford Truss and a Long Truss. Without interior photographs, it isn’t easy to discern. Regardless, the West Henniker Bridge stood over the Contoocook River until it was replaced with a metal truss bridge in 1915.

The United States Census records list Whitney’s occupation as a carpenter throughout his lifetime. The diversity of his talents undoubtedly provided him with steady work and landed him a side business as an undertaker.

In the early nineteenth century, woodworkers had the skills necessary to build coffins for the dead in their community. At the time, the local undertaker would take the measurements for a coffin, construct it, and return it to the home for the deceased to be laid out for viewing. Family members would dress the deceased in their best clothing, and the body would lie in the coffin for several days until the funeral. Sometimes, doorways or windows were too narrow to accommodate a coffin and had to be temporarily removed. Records show Whitney had been making coffins since at least 1840, when he was paid $2 for a casket. When he retired from bridge building, undertaking became his primary business.

In addition to his carpentry skills, Whitney was a talented musician. For most of his life, he sang in the Congregational Church choir and was the choir director for many years. He “exhibited a good deal of the taste for music for which he was noted in his younger days” (Cogswell 1880).

Whitney was a member of Henniker’s first brass and reed band. Formed in the winter of 1836-1837, the band consisted of thirteen original members, with Whitney playing the clarinet and his brother-in-law Dutton Woods playing the bugle. As this type of music was just coming into vogue, the Henniker Band was in demand to play at “trainings and muster days.” The band first played in public in the fall of 1838 in New Hampton and soon “furnished themselves with a ‘band wagon’ and a large tent for camping purposes. For several years, and, in fact, until the militia was disbanded in 1851, they attended several musters and furnished music for some of the best companies of militia within fifty miles of their home” (Cogswell 1880).

Whitney was also civically minded and served the town of Henniker as the tax collector in 1843, selectman in 1847 and 1849, school committee member in 1866, and town treasurer in 1876.

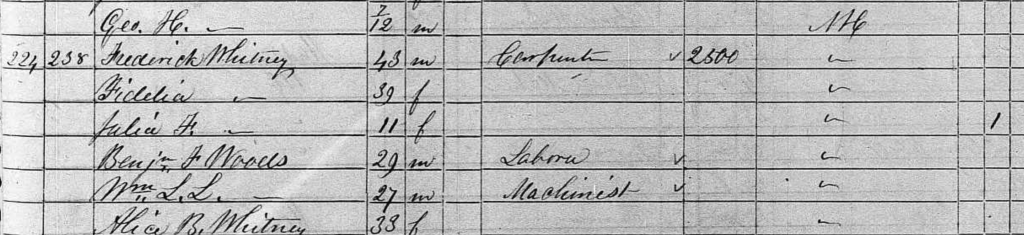

It seems Whitney was equally committed to his family, many of whom were befallen by tragedy. The 1850 census shows that in addition to Frederick, Fidelia, and Julia, the Whitney household also included Fidelia’s brothers, Benjamin Franklin Woods (1820-1893) and William Lewis Lawrence Woods (1823-1900), and Frederick’s youngest sister, Alice B. Whitney (1816-1854).

Alice seems to have experienced some type of mental illness or disability. In the last two years of her short life, she appears in town reports as a pauper, and the town pays Frederick and other community members for her care. In 1854, she was reported as having a “sickness” and died shortly thereafter. Her death record indicates she died of “nervous debility.” She was 38.

Whitney’s oldest brother, Asa (1800-1858), described as “a hard-working honest man,” sang alongside his brother in the church choir. In 1850, his first wife, Patty Rice, died after falling from the scaffolding in her barn. That same year, he married Mary Long Childs (1810-1896), sister of Horace Childs. Eight years later, Asa was killed after being struck by a falling tree in the woods. He was 57.

On June 2, 1857, his wife, Fidelia, died of consumption. She was 45 years old. One can only imagine the duality of Whitney’s role as a grieving man and the town undertaker. Did he craft the coffins for his beloved family?

Whitney remarried on May 12, 1864, to widow Helen “Hannah” Badger Carter (1819-1909) of Warner. Hannah’s first husband, merchant William S. Carter (1816-1851), died at age 34, leaving her with two young boys. The youngest, Henry, died of typhoid fever in 1860 at age 12. Her oldest, William Scott Carter (1842-1931), would become a prolific member of the Lebanon community.

Shortly after their marriage, Frederick and Hannah moved to a house next to the Congregational Church. The home had been built by Napoleon Bonaparte Connor (1810-1883) in 1837 after the previous house had been struck by lightning and burned. Records indicate that Whitney bought the home at what is now 25 Maple Street sometime “after the Civil War.” The property is three lots over from the 1835 home of Horace Childs.

After moving to the Maple Street property, he purchased a vacant schoolhouse and relocated it behind his house as a coffin-making shop. Notes on file at the Henniker Historical Society state, “he was a carpenter whose side business was undertaking…undertakers made their own coffins. Mr. Whitney did not employ help.”

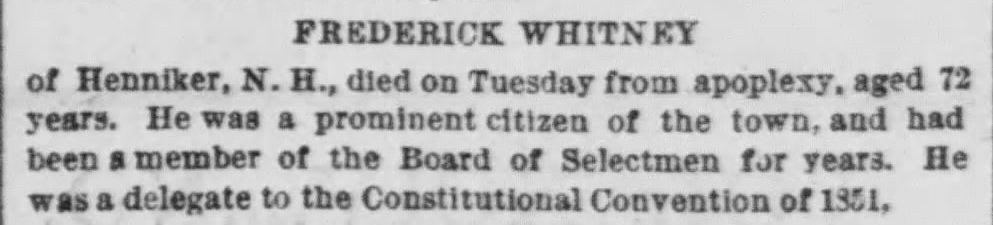

Frederick Whitney died on May 20, 1879, at age 72, of apoplexy, or what would be called a stroke today. His wife, Hannah, moved to Lebanon to live with her son. She would outlive Whitney by thirty years.

After his death, Hannah deeded the property to Whitney’s daughter. Julia had married Civil War soldier William Odlin Folsom (1838-1920) in 1869. Folsom was a widower; his first wife, Caroline “Carrie” Fidelia Foster (1835-1866), had died three years earlier of consumption. Carrie was the daughter of Whitney’s older sister, Lois (1803-1852) and Zebulon Foster (1797-1897). She and Julia were first cousins.

Folsom was a merchant and, much like his father-in-law, served the town of Henniker as treasurer and selectman. After Whitney died, Folsom took over the undertaking business but not the coffin-making side. He used the coffin shop as a storehouse and sales office for the business. In 1873, the Folsoms welcomed their only child, a daughter named after William’s late wife and Julia’s cousin, Caroline “Carrie” Eliza. Carrie died in Wellesley, Massachusetts, in 1961.

Frederick Whitney was regarded as a “kindly, genial man, much loved by his fellow townsmen.” For decades, Whitney crafted a final resting place for many of his neighbors and family members. Those coffins, like his covered bridges, cannot be seen today. But their significance remains.

References

Historical photos were used with permission from Covered Spans of Yesteryear and the National Society for the Preservation of Covered Bridges.

Special thanks to Sue Fetzer, Marc McMurphy, and Martha Taylor, Henniker Historical Society; Todd Clark, Bill Caswell, and Scott Wagner from the National Society for the Preservation of Covered Bridges; and Catherine Dart, Whitney’s second-great granddaughter.

Biographical Review Publishing Company. 1897. Biographical Review; containing life sketches of leading citizens of Merrimack and Sullivan counties, N. H. Boston: Biographical Review Publishing Company.

Browne, George Waldo. 1921. The History of Hillsborough, New Hampshire, 1735-1921: History and description. United States: John B. Clarke Company, printers.

Childs, Francis Lane. “Genealogies on file at the Henniker Historical Society.”

Cogswell, Leander Winslow. 1880. History of the Town of Henniker, Merrimack County, New Hampshire. Henniker, NH: Republican Press Association.

Harriman, Walter. 1879. The History of Warner, New Hampshire, One Hundred and Forty-Four Years from 1735–1879. Concord, NH: Republican Press Association.

Hillsborough-Enterprise. 1899. Hillsborough-Enterprise, July 22, 1899.

Hillsborough Messenger. 1899. An Old Landmark Gone. Hillsborough Messenger, July 6, 1899.

Goodell, John. 1899. Letter to the Editor. Hillsborough Messenger, July 13, 1899.

Town of Henniker. 1840, 1847, 1848, 1853, 1855, 1866. “Annual report of the town of Henniker, New Hampshire.” Henniker, NH.