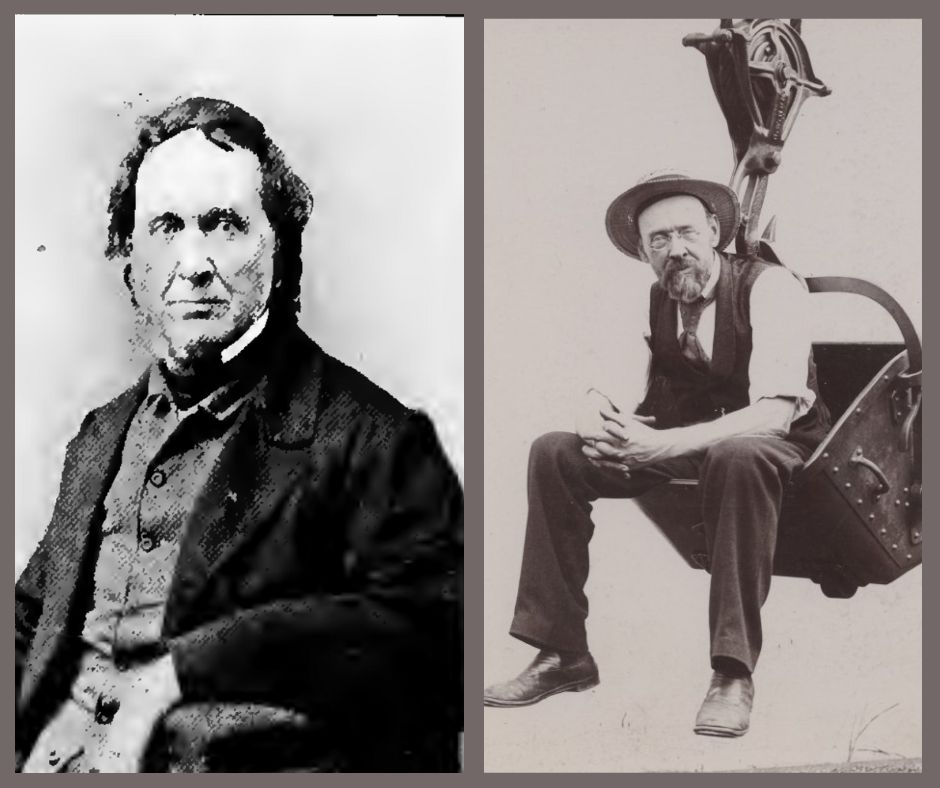

Part One – Sanford Granger (1796–1882)

The Granger story in New Hampshire begins with Eldad Granger (1766-1866) and his wife, Sarah Holmes (1771-1852). Natives of Connecticut, Eldad and Sarah moved north to the Connecticut River Valley and settled in Chesterfield, New Hampshire, shortly after their marriage in 1786.

Eldad worked as a mechanic and wheelwright and, for a time, as a boat captain on the ferry boats on the Connecticut River. At the end of the eighteenth century, the family moved a few miles north to Westmoreland, where Eldad built a house. He also purchased several mill properties on Mill Brook, which he rebuilt and combined into a single mill operation around 1800. The mill became known as the Granger Mill, and the area around it was known as Granger Hollow.

He and Sarah had fifteen children: Lucinda (1788-1822), Luther (1791-1867), Sabra (1793-1793), Sabra (1794-1849), Sanford (1796-1882), Mary (1798-1881), John (1800-1805), Elihu (1802-1896), Maria (1804-1884), Miranda W. (1808-1892), Nancy (1808-1861), John J. (1810-1826), Lucy H. (1814-1900), Daniel H. (1817-1841).

Eldad was a respected member of the Westmoreland community and lived to be almost one hundred years old; he missed being a centenarian by fourteen days when he died on March 2, 1866. Following his death, he was remembered for having voted in “every Presidential election from George Washington to Abraham Lincoln” and for some unusual physical features. He was described as “never sick in his life… he used tobacco and spirits in moderation …he was spare and slight in figure and wiry and muscular. He had what is known as a double set of teeth all around, and at his death, they were in perfect condition” (Granger 1893).

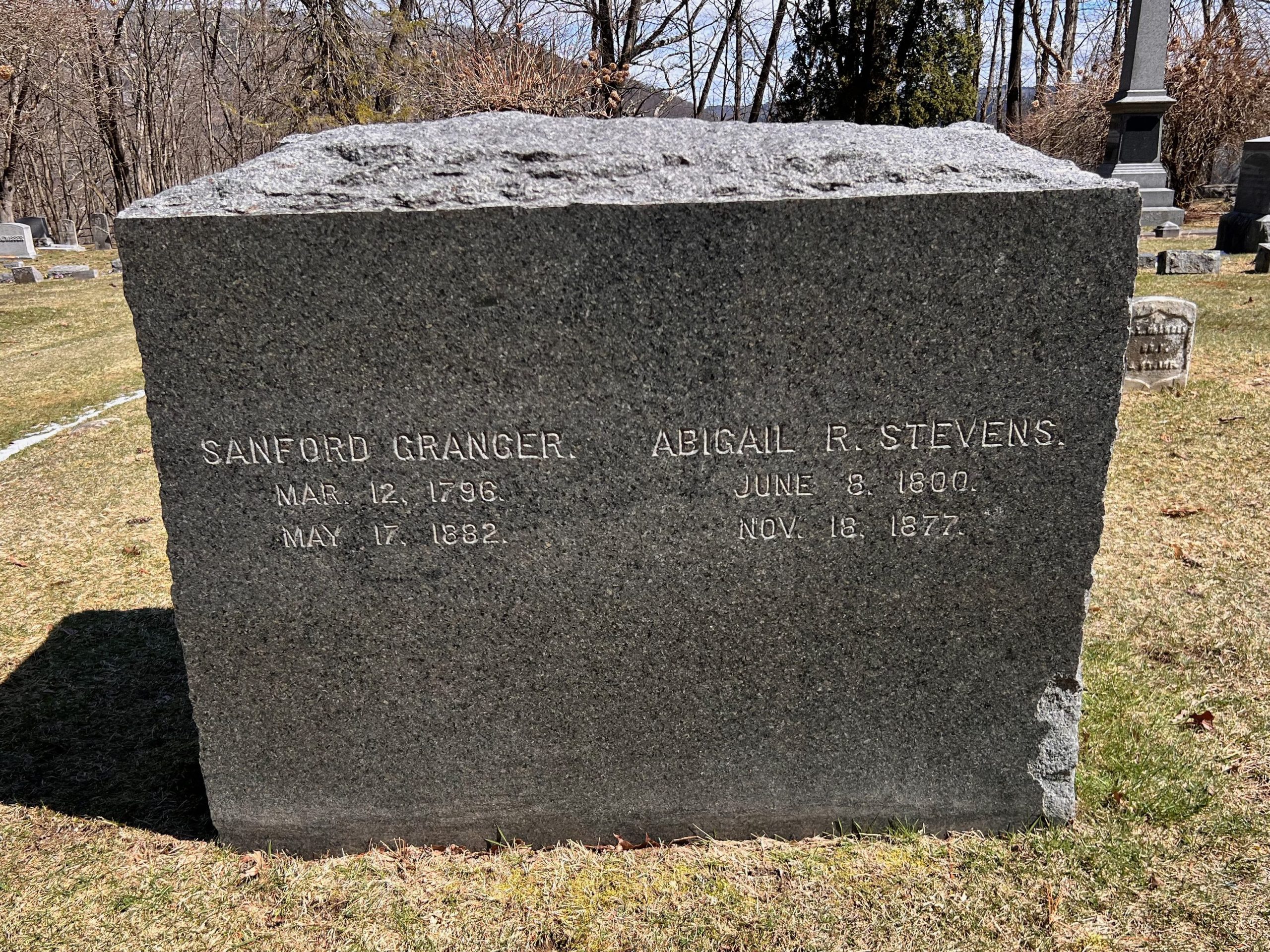

Eldad left his Westmoreland property to his son, Sanford, who sold a parcel to George H. Britton (1835-1891) in 1875 and eighteen acres to Willard S. Shaw (1813-1895) in 1878. The 1967 town history indicates that the mill had “gone to decay” by 1885 and that “no recognizable remains of the Granger dam or mills have been found” (Westmoreland History Committee 1976). The Granger home no longer exists, and in 2006, the road bearing their name was relocated. All that remains of the Grangers in Westmoreland are family tombstones in the North Cemetery.

The Granger bridge building legacy begins with Eldad’s fifth child and second son, Sanford. He was born on March 12, 1796, and according to his birth record, he was born in Westmoreland. Various biographies list his birthplace as Chesterfield or across the Connecticut River in Bellows Falls, Vermont. Regardless of where he came into the world, Sanford inherited his father’s propensity for mechanics and millwork.

Around 1820, the 23-year-old Sanford moved from Westmoreland to Bellows Falls, a village in Rockingham, where he bought a former mill site. Sanford erected a dam down the river from some other mills. But before he could build his sawmill, a freshet destroyed his dam, “causing so great financial loss that he abandoned the project” (Hayes 1907).

On February 26, 1826, at age 30, he married Abigail R. Stevens (1800-1877) in the neighboring town of Westminster, Vermont. The couple had five children: Albert Sanford (1834-1922), Harriet Abigail (1837-1880), Edwin (1843-1843), Edward Loring (1844-1894), and Mary Geyer (1846-1846).

A few months after the wedding, Sanford purchased a sawmill at Gageville, a village in Westminster alongside the Saxtons River, which he owned and operated for many years. Another freshet would threaten his livelihood in April 1826. “Mr. Granger and his family had retired to rest, supposing the water was falling and the danger past. With this security the inmates of the house had sunk into sleep, and so sudden was the vent, that they never heard the crash nor discovered their loss until morning. Mr. Granger had in the mill between sixty and seventy dollars worth of joiner’s tools when carried away” (Hayes 1907).

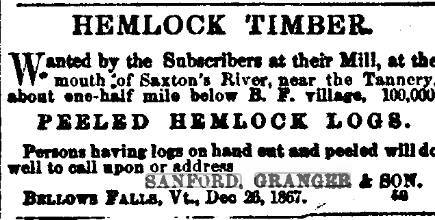

Granger developed the sawmill into a profitable lumber business called S. Granger & Son. Also on the property was a brickyard. Sanford is credited with providing bricks to the Vermont Valley Railroad to construct a train station near the Cheshire and Sullivan Bridges. The two-story brick station was built in 1851 and destroyed by fire in 1921. The property would later become the site of the Gage Basket Factory and is now home to the abandoned Chemco building. While the Granger properties are long gone, the road that ran through it still bears their name.

Sanford was a founding member of the Methodist Church in Bellows Falls. In 1835, he bought an abandoned one-story brick schoolhouse on Westminster Street as temporary quarters for the congregation. Later that year, Sanford and two other businessmen financed the building of the new Methodist Church on Atkinson Street. In return, he was given the choice of pews. Sanford served as one of the church’s first trustees and remained a lifelong congregant, even leaving $500 to the church in his will. Various reports indicate that Sanford actually built the building itself, but that is not substantiated. The building was demolished in 2021.

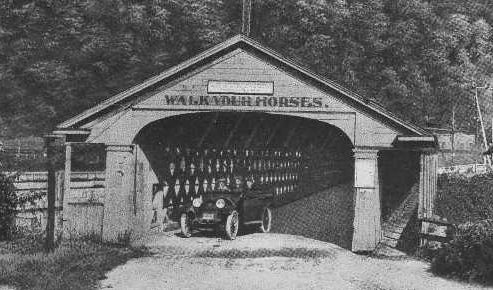

Sanford’s covered bridge career seemingly began in the Saxtons River village on Hartley Hill Road. Sanford constructed a bridge interchangeably called the Village, Saxtons River, Sawmill Bridge, and even the Brookline Bridge. It is unclear when this bridge was built, but it was destroyed by a freshet on Monday, October 4, 1869. It was replaced the following year; the builder is unknown.

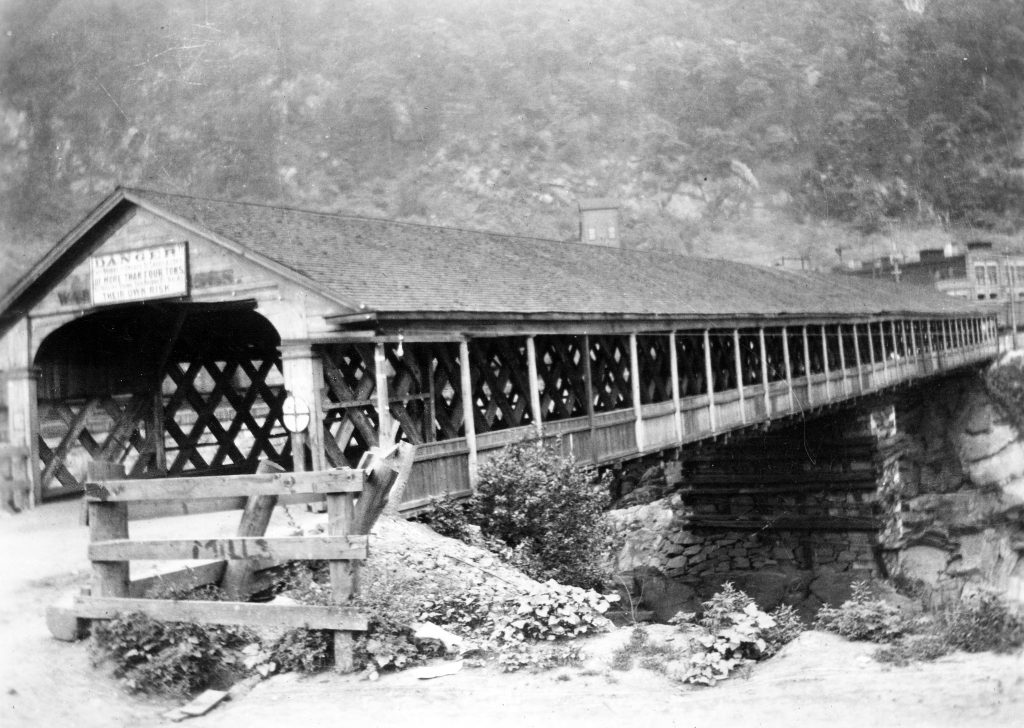

In 1835, Sanford built another covered bridge over the Saxtons River, this time just down the river from his mill in Gageville. Sanford himself petitioned the county court for both a road and a bridge at this location. In July 1835, the town decided to build both the road and the bridge, given that Sanford would “agree to pay $200 toward the road and build the bridge aside from the abutments ‘on the plan of the one which the said Granger built across Saxtons river’ for $6 per running foot” (Springfield Reporter 1941). Known interchangeably as Gageville or Grangers Bridge, this 118’ Town lattice truss bridge stood until it was destroyed by arson on August 13, 1967.

Sanford was contracted by Aaron Willson (1795-1846) and Oren Dickinson (1809-1890) of Keene to assist in building the West Street Bridge in 1837. “The bridge was laid out and framed by a man named Granger, from Westminster, Vt. The pins that hold the lattice work are of white oak” (Keene Evening Sentinel 1900). When the bridge was taken down in 1910, it was reported that the planks were as “good as ever” (Keene Evening Sentinel 1900).

In 1840, architect and builder Captain Isaac Damon (1781-1862) of Northhampton, Massachusetts, was hired to build a new covered bridge connecting Bellows Falls and Walpole over the Connecticut River. Damon had previously built many covered bridges across the Connecticut River and several alongside his business partner, Lyman Kingsley (1800-1862). Damon and Kinglsey employed Sanford as part of the project. “Sanford Granger, as a builder, had a prominent part in building the new bridge and furnished lumber for it in connection with the Elwells of Langdon” (Hayes 1907). Robert Elwell (1807-1884) was a lumberman across the river.

The crew replaced an uncovered bridge constructed in 1795 by Colonel Enoch Hale (1733-1813). At the time, this structure was considered one of the strongest and most elegant bridges in America, but by 1840, it was in rough shape. Damon and his crew built the new bridge fifteen feet above the old one. Travelers utilized the old bridge until the new bridge opened; then, workmen “cut away the old bridge after the completion of the new one in July 1840. The old frame was allowed to fall to the rocks many feet below and later was carried away by high water” (Hayes 1907).

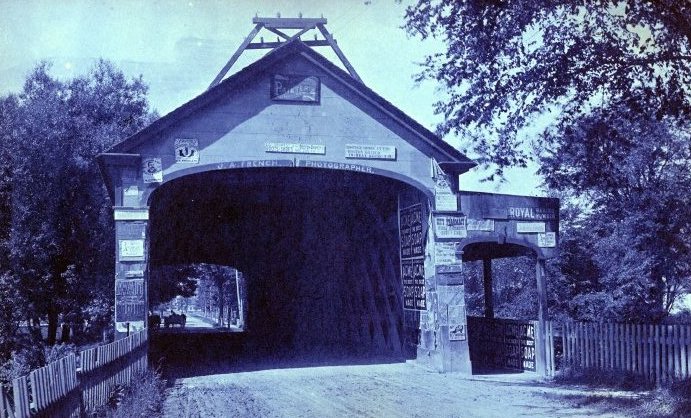

This 262’, two-span, Town lattice truss bridge was known as the Tucker Toll Bridge. Financed by Bellows Falls businessman Nathaniel A. Tucker, the bridge collected tolls until 1904. It was replaced in 1930 by the Charles N. Vilas Bridge, which has been closed since 2008.

In 1843, Sanford was hired to raise and lengthen the Lewis Bridge in Westminster. The 1838, 41’ bridge was damaged by high water that washed out one abutment. Sanford lengthened the bridge to 65’ and was paid $170 for the job. The Lewis Bridge was replaced in 1953.

For almost two decades, it appears Sanford took a hiatus from building covered bridges and turned his attention to buildings. In 1855, Sanford tore down that Westminster Street schoolhouse and constructed a three-story building called the Granger Block. According to Hayes’ History of Rockingham, several Native American skeletal remains were exhumed during the construction of the building. The Granger Block is often referred to as a brick building, but it appears to have been constructed with a wood frame with brick veneer.

Sanford moved his family to the second floor of the Granger Block. The ground floor was used as a store for many years, housing businesses such as D. W. Brosnahan Grocers, H. W. Redfield Grocers, M.B. Kelley Grocers, F.B.F. Grocers, Harty & Keane Grocers, G.B. Albee Plumbing, F. P. Hadley’s Stove and Tinware, C.E. Whitman’s Lenten Goods, A. F. Winnewisser’s dry goods store, Bailey Brothers piano warehouse, and Connors’ Store. The building was eventually purchased by Eugene Cray (1888-1965) in 1930, officially ending the Granger affiliation. The Cray Block was ultimately expanded to include a bowling alley on the top floor and modern shops below. The building was destroyed by fire on February 19, 1984. A parking lot exists today in its location.

In 1860, the Bellows Falls Times reported that Sanford had “taken the job of building the block on Westminster street for C. E. Chase and son” (Bellows Falls Times, 1860).

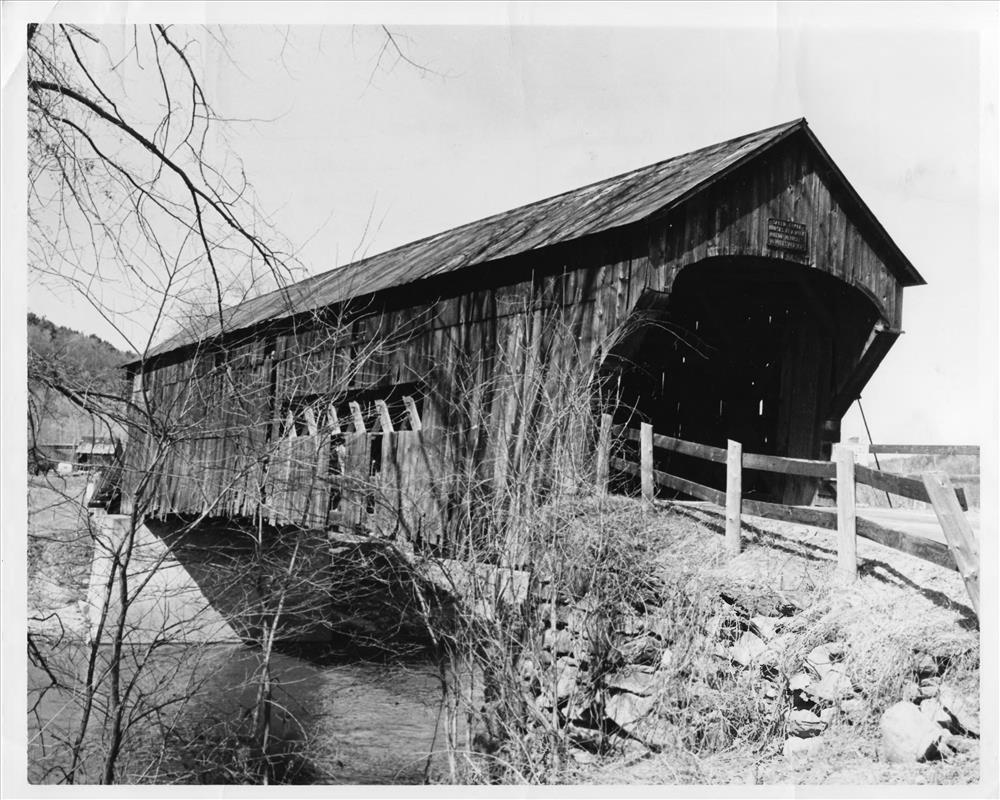

In 1867, Sanford returned to building bridges with the construction of the Hall or Osgood Bridge in Rockingham, just east of Saxons Village. The 1973 National Register for Historic Places describes the bridge as “a single span supported by two flanking timber Town lattice trusses. At each corner of the bridge an iron buttress extends from an extended floor beam to the upper side of the bridge, providing lateral support for its superstructure…. The bridge is 117 feet long and 15 feet wide, with a 12-foot roadway” (Henry 1973).

The Hall Bridge stood until it collapsed under the weight of a truck overloaded with stone on October 2, 1980. A replacement bridge was erected in 1982 by Milton S. Graton of Graton Associates, Inc. of Ashland. Graton’s bridge stands today.

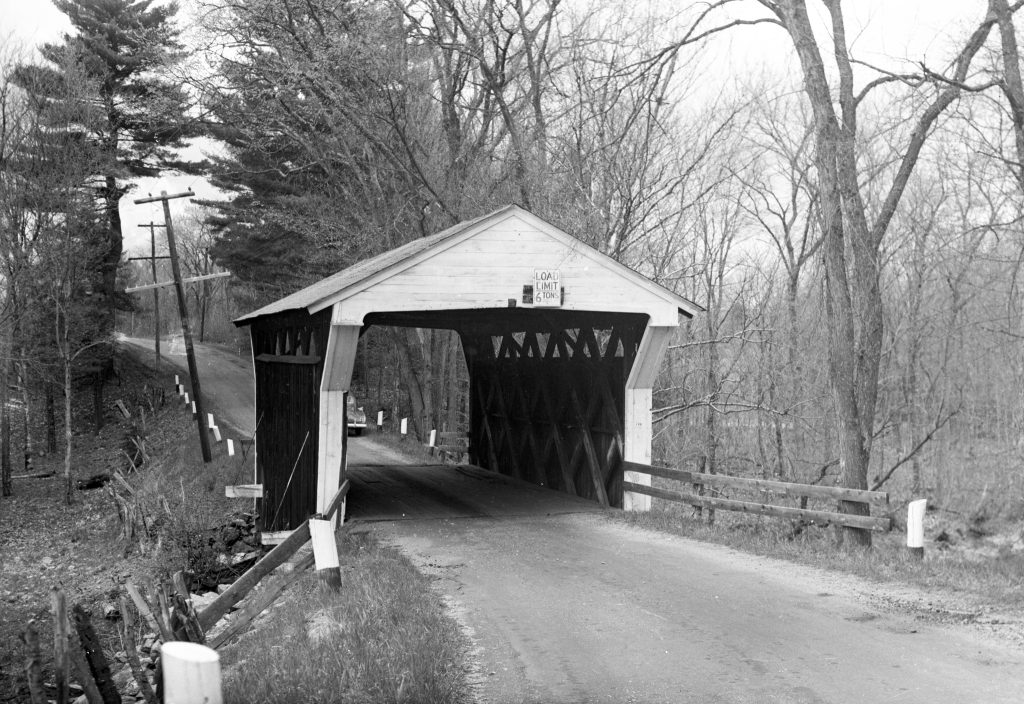

The following year, Sanford constructed the Worrall Bridge over the Williams River in Rockingham. This 83’ Town lattice truss bridge is the oldest surviving nineteenth-century covered bridge in Windham County and the last of Sanford Granger’s covered bridges to exist. It has been reinforced over the years and survived damage from both Tropical Storm Irene in 2011 and the major flooding of July 2023.

The year 1870 marked the construction of the last of Sanford Granger’s covered bridges. The County Farm Bridge, an 80’ bridge over Partridge Brook in Westmoreland, was reportedly built by Sanford. The bridge stood until it was destroyed by the Great Freshet of 1936.

That same year, Sanford built the Bartonsville Bridge in Rockingham. This 151’ Town lattice truss was constructed to replace a covered bridge that was destroyed by the freshet of 1869. The Bartonsville Bridge stood over the Williams River until it was destroyed during Tropical Storm Irene in 2011. (You can see the tragic collapse as recorded by Susan Hammond and shown on CBS News here. Be forewarned; it’s tough to watch.) The bridge was rebuilt in 2012 by Cold Water Bridges.

Local communities hired Sanford to make repairs on their bridges. In 1875, Sanford was paid $123.97 for repairing the Walpole and Westminster Bridge, which had been built only five years before. Alstead paid him $57.83 for “work and lumber on bridge” (Town of Alstead 1879) in 1879 and for “use of capstan and jacks for raising bridge” (Town of Alstead 1882) in 1882. The specific bridges are not identified.

Sanford’s second act of bridge building and repairs began when he was 71 years old. It also coincides with his son Albert’s return to Bellows Falls. It’s more than likely the two worked together on these projects.

Sanford’s wife, Abigail, died on November 19, 1877, of pneumonia. She was 77 years old. Sanford died five years later, on May 17, 1882, at 86, also of pneumonia. They are buried together in Oak Hill Cemetery in Bellows Falls.

It appears Sanford had been preparing his funereal vessel well in advance of his passing. According to an article in the Rutland Daily Herald, Sanford would closely watch “the lumber passing through his hands and whenever he found a particularly nice board he laid it aside and later he fashioned for himself his last resting place… old men, boys then, tell of his inviting them up to his apartment and taking them to a particular room in the rear where he showed them the coffin…the elegant appearance of the selected woods made indelible impressions, on their minds as well as the gruesome use to which it was to be devoted” (Rutland Daily Herald 1930).

Sanford was remembered as “a strong advocate of temperance” and as an “ardent abolitionist” (Hayes 1907). He was an active participant in the Underground Railroad, assisting in bringing enslaved people to freedom across the border in Canada. His son, Albert, recounted seeing Black people “come from the hay mow and go into the house in the morning with a pail for breakfast so freely given” (Hayes 1907).

It is important to note that many of Sanford’s covered bridges are referred to as “Granger Bridges,” which leads one to assume that a specific truss design may have been employed. It has been speculated that Sanford applied for a truss patent in 1833. However, there is no record of a patent for a bridge design attributed to Sanford Granger. If it existed at all, his patent request is believed to have been destroyed in the fire in the patent office on December 15, 1836. Most of Sanford’s bridges employed a Town lattice truss, a fact reinforced by Victor Morse in “Windham County’s famous covered bridges” in 1960.

Part Two – Albert Sanford Granger (1834–1922)

Albert Sanford Granger was born on November 10, 1834, in Westmoreland, the first child of Sanford and Abigail. Very little is known about his childhood. However, by the late 1850s, Albert was living in Concord, New Hampshire, where he worked as a gas fitter. On March 16, 1857, at age 22, he married Loretta E. Carpenter (1835-1870) of Springfield, Massachusetts. He moved his young wife to the capital city with him.

Albert and Loretta had five children: Clement Alfred (1834-1922), Carrie Augusta (1861-1953), Rose B. (1863-1950), Ruth Elizabeth (1865-1949), and Sanford Thomas (1868-1870).

In 1861, Albert moved the family to Springfield, Massachusetts, when, according to his daughter Carrie’s obituary, he had a contract to build the South End Bridge over the Connecticut River, which was “to be similar to others he had constructed in Vermont and New Hampshire” (Transcript-Telegram 1953). Albert was 27 years old at the time. It is unclear which covered bridges Albert constructed prior to 1861. He was too young to have assisted his father in the 1840s. Either this recollection is inaccurate, or there are more Granger covered bridges that were constructed. More research is needed.

Regardless, the Civil War caused the bridge project to be postponed, and Albert took a job at the Springfield Armory, where he aided in the manufacture of firearms for the Union. He worked as an inspector, examining guns for any defects. Weapons bearing the US inspector marking of ASG were personally inspected by Albert.

In 1867, Albert and his family relocated to Bellows Falls. The 1870 census indicates he worked as a bridge conductor and resided with his wife, Loretta, his five children, his mother-in-law, and two others. His infant son Sanford died on April 21, 1870, of brain inflammation, and his wife Loretta died on June 16. Her cause of death is unknown. She was 34 years old.

In 1869, the nearby town of Langdon, New Hampshire, lost one of its covered bridges in the Great Freshet. The Cold River Bridge needed to be replaced. Handwritten town records at the Langdon Town Office mentioned the bridge in a notation dated November 20, 1869, regarding a new highway. A new roadway petition had been brought forth on October 25 after the previous highway was destroyed, presumably by the flooding. The measurements of the new roadway specifically mention Calvin Smith’s barn and “four rods and four links to the center of the face of the new abutment on the north side of Cold River” (Town of Langdon 1869).

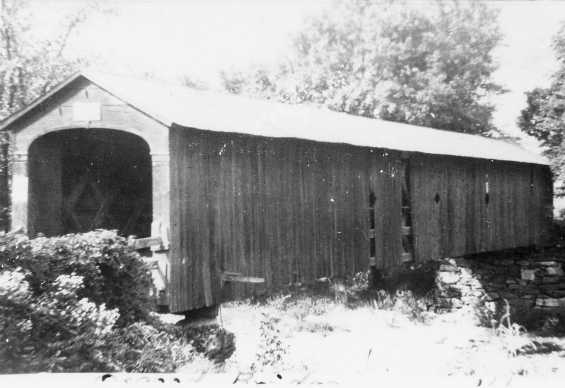

A new covered bridge was constructed for $450, using virgin timber from nearby Fall Mountain. Several accounts, including the National Register of Historic Places application, indicate Albert built the bridge. However, town records could not be located to prove this assertion definitively. Today, the bridge is called the McDermott Bridge and stands on Crane Brook Road.

The following year, Albert constructed the Jones or West Bridge in Saxtons River Village, less than two miles from his father’s first covered bridge. The Jones or West Bridge was originally a Queenpost pony truss with later reinforcing additions, resulting in the appearance of Kingpost trusses, and was 89 feet long (Wagner 2024). The bridge was razed in 1964.

In 1874, the town of Langdon once again hired Albert for bridgework, this time to replace the Prentiss Bridge over Great Brook. The town of Langdon paid $1,062.09 for the project. Granger himself was paid $197.50 for labor, $34.97 for lumber, bolts, and spike, and $23 for the use of a derrick; nineteen other men were paid for labor and supplies (Town of Langdon 1875).

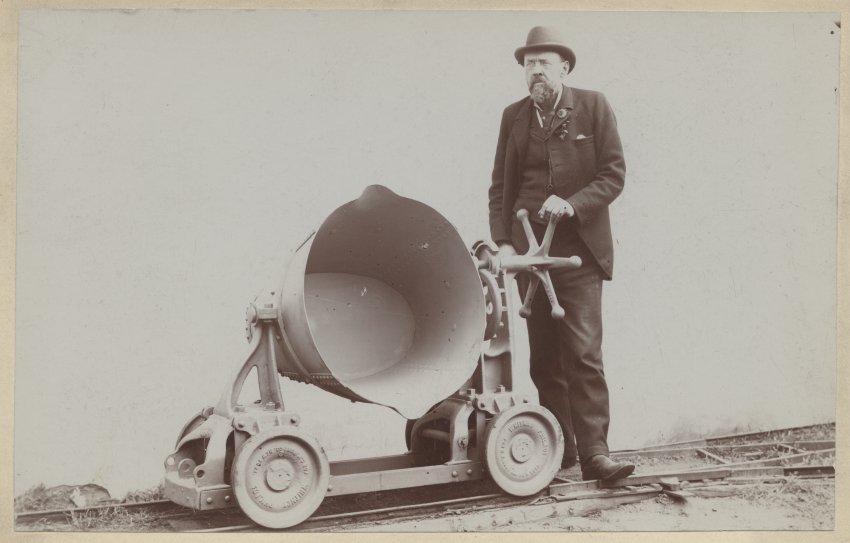

After six years as a widower, Albert married Sarah E. Hodgkin (1846-1880) on October 29, 1876, in Framingham, Massachusetts. That same year, the Grangers relocated to Brooklyn, New York, where Albert took a job as the machine shop foreman at the C.W. Hunt Company in Staten Island, one of the largest manufacturers of industrial equipment, such as hoisting engines, steam shovels, and coal-handling machinery. The photos of Albert on this page were taken by the C.W. Hunt Company.

The 1880 census shows Albert and Sarah residing at 605 Pacific Street in Brooklyn, but Albert’s children are not listed. Clement is listed in Brooklyn as a boarder on Jay Street and working as a machinist. Clearly, his younger three children were there as well. Ruth would later graduate from PS 15 in Brooklyn and became a school teacher, principal, and superintendent in the NYC school system. She married Captain Arthur N. Gray (1862-1949) and, after her retirement, moved to Agawam, Massachusetts. Rose also taught school in Brooklyn for many years before retiring to Florida. She never married. Daughter Carrie would marry Israel M. Charlton (1860-1931) in Massachusetts and make her home there.

By the end of that year, Albert would once again be a widower. Sarah died of consumption on December 8, 1880. Like Albert’s first wife, she was 34 years old. A month later, on January 8, 1881, his only surviving son Clement also died of consumption. He was 23 years old.

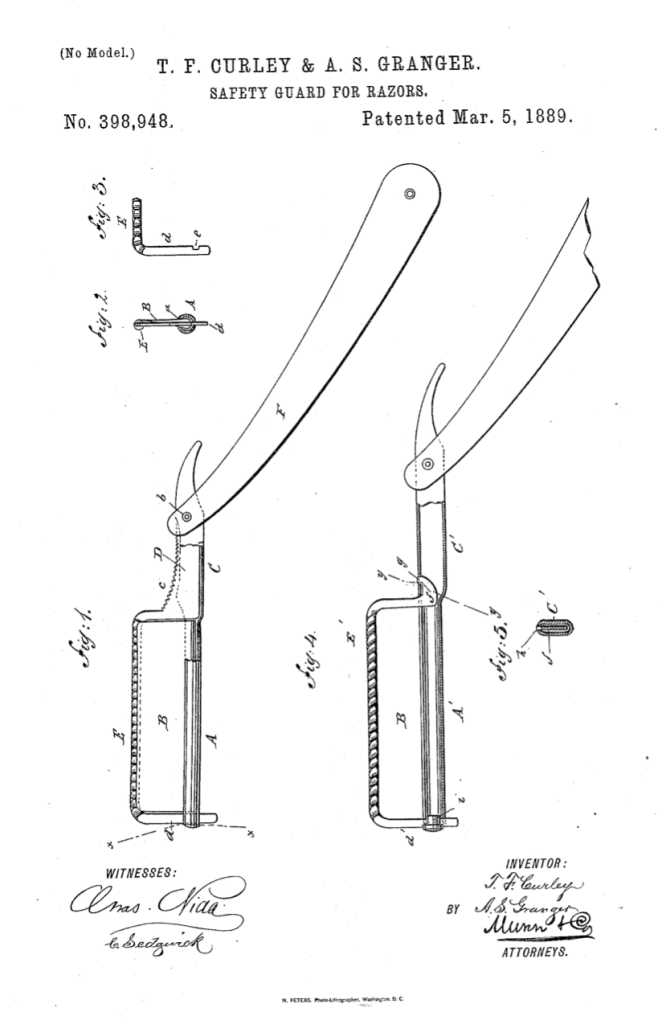

In addition to his work as a machinist, Albert was also an inventor and held several patents for a variety of products, including a pen holder, patented in 1859, a machine for cutting teeth of rack bars, patented in 1885, and a check perforator, patented in 1899. More notably, Albert partnered with safety razor inventor Terence F. Curley to improve upon his earlier patent. Albert and Terence were issued a patent in 1889 for the Curley Ideal Safety Razor. Promising a “sliding diagonal shave” and claiming to be “the one razor that will not let you scrape your face,” the Curley Ideal Safety Razor was “unconditionally guaranteed” (J. Curley & Brothers).

When Albert was 54, he got married for the third time. His wife was Adelaide C. Hayes (1837-1903), a native of Farmington, New Hampshire, who had been working as a New York City school teacher for several years. The two married on January 25, 1889, in Manhattan. Adelaide’s 1898 will indicates she owned property on Douglas Street in Brooklyn, but the couple was living on Staten Island.

In 1892, Albert served as a juror for The People vs. Michael J. O’Connell. During his juror testimony, he indicated he worked as a mechanical engineer. Incidentally, O’Connell was charged with murdering his wife; Albert and eleven others found him guilty of manslaughter in the second degree.

By 1900, Albert and Adelaide were living in Washington, DC. The census shows the pair as boarders at 516 Ardmore 13th St. NW. Albert’s occupation is listed as mechanical engineer. Why they were in the nation’s capital is unclear.

The couple returned to Staten Island, where Adelaide died on November 5, 1903. She was 66 years old. Adelaide was laid to rest back in New Hampshire, and Albert moved north to live with his daughter, Carrie and her husband, Israel M. Charlton (1860-1931). The family lived on Riverdale Street in West Springfield, Massachusetts, in a home owned by Albert.

The 1910 census shows Albert still working as a millwright in a machine company at age 75. Ten years later, he had seemingly retired.

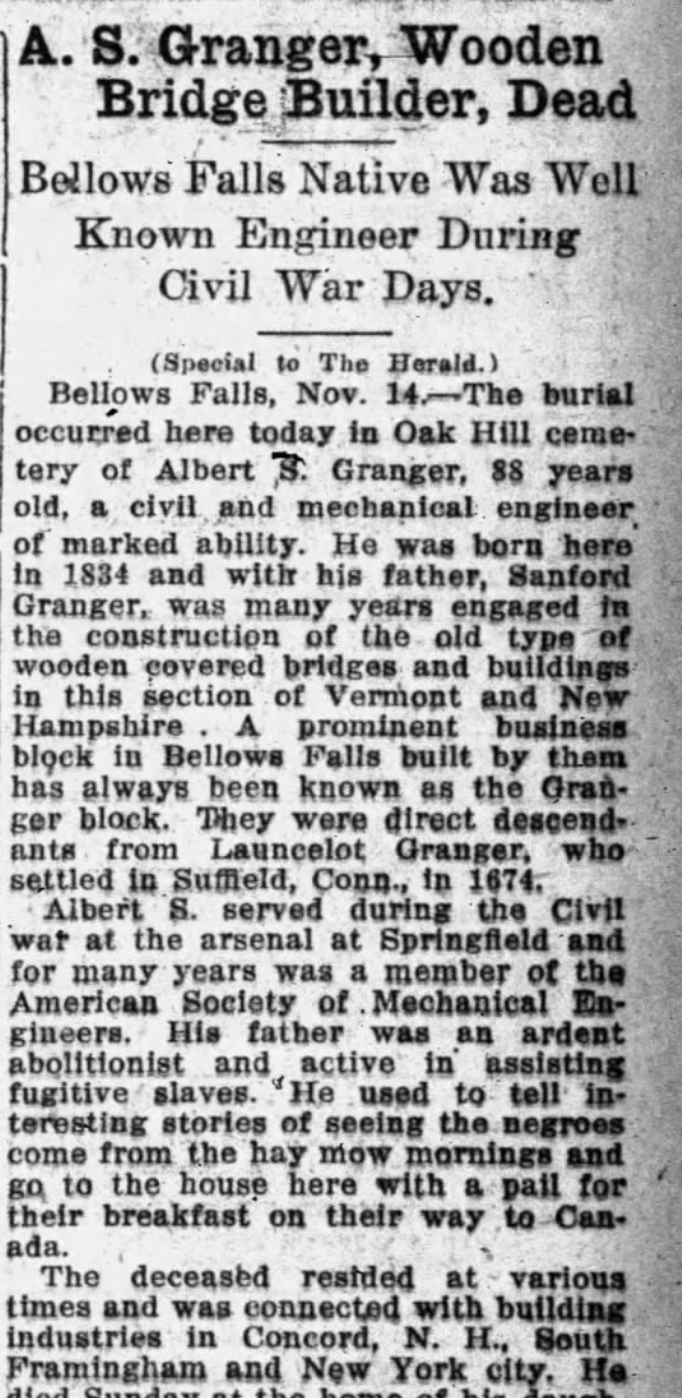

Albert died in West Springfield on November 12, 1922, at the age of 88, after a four-week illness. The funeral was held at his home, and the Reverend Allan K. Chalmers officiated. Albert is buried alongside his first wife, Loretta, in the Oak Hill Cemetery in Bellows Falls.

His obituary remembered him as an “inventor and a civil and mechanical engineer of marked ability” and that, along with his father, he built “many of the covered bridges in Vermont in New Hampshire” (Transcript-Telegram 1922).

Albert Granger’s work can be seen today in Langdon’s two existing covered bridges, the McDermott and the Prentiss. Fortunately, the town of Langdon opted to bypass both bridges instead of removing them. After years of neglect, both were restored with monies raised by the Langdon Covered Bridge Association. The Prentiss Bridge was restored by master bridgewright Arnold M. Graton of Arnold M. Graton Associates, Inc. of Holderness, and rededicated in 2002. The McDermott Bridge was rehabilitated by Daniels Construction, Inc. of Ascutney, Vermont, and rededicated in 2008.

References

Historical photos not part of the author’s collection were used with permission from Historic Richmond Town, Mac McClaren, Covered Spans of Yesteryear, and the National Society for the Preservation of Covered Bridges.

Special thanks to Walter Wallace, Coordinator, Rockingham Historic Preservation Commission; David Deacon, SUNY Oswego; Larry Clark, Vice President, and Cathy Bergmann, President, Bellows Falls Historical Society; Pamela Johnson-Spurlock, Reference and Historical Collections Librarian, Rockingham Free Public Library; Carli DeFillo, Collections Manager, Historic Richmond Town, Staten Island, NY; Carla Westine and Rachael Spafford, Chester Vermont Historical Society; Tina Gilbert Tidd, and Dianna Hart Wilson; Scott Wagner and Bill Caswell, National Society for the Preservation of Covered Bridges.

Allen, Richard Sanders. 1962. Rare Old Covered Bridges of Windsor County. Brattleboro, VT: The Book Cellar.

Argus and Patriot. 1883. “Bellows Falls Briefs.” Argus and Patriot. July 11, 1883, 2.

Bacon, Edwin Monroe. 1906. The Connecticut River and the Valley of the Connecticut: Three Hundred and Fifty Miles from Mountain to Sea; Historical and Descriptive. United Kingdom: G. P. Putnam’s Sons.

Bellows Falls Times. 1860. “Local Matters.” Bellows Falls Times. May 25, 1860.

———. 1863. “Local Matters.” Bellows Falls Times. October 2, 1894.

———. 1867. “Local Matters.” Bellows Falls Times. December 26, 1867.

———. 1894. “Business Cards.” Bellows Falls Times. June 21, 1894.

———. 1894. “Ed Gould’s Apartments in the Granger Block Burned Out.” Bellows Falls Times. December 13, 1894.

CBS News. 2011. “Caught on tape: Irene’s flooding takes out bridge.” Amateur footage provided by Susan Hammond. Accessed March 17, 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZEs8ubAw7a8.

Conwill, Joseph D. 2004. Vermont Covered Bridges. United States: Arcadia.

Curley, Terence F., and Granger, Albert S. 1889. Safety-Guard for Razors. US Patent 398,948. Issued March 5, 1889.

Encyclopedia of Massachusetts, Biographical–genealogical. 1916. United States: American Historical Society (Incorporated).

Granger, A. 1859. Pen Holder. US Patent 23,366. Issued March 29, 1859.

Granger, A. 1885. Machine for Cutting Teeth of Rach Bars. US Patent 313,201. Issued March 3, 1885.

Granger, James Nathaniel. 1893. Launcelot Granger of Newbury, Mass., and Suffield, Conn: A Genealogical History. United States: Higginson Genealogical Books.

Griffin, Simon Goodell. 1980. The History of Keene, New Hampshire. United States: Heritage Books.

Hayes, L. S. (1907). History of the Town of Rockingham, Vermont: Including the Villages of Bellows Falls, Saxtons River, Rockingham, Cambridgeport, and Bartonsville, 1753-1907, with Family Genealogies. United States: The Town.

Henry, Hugh H. 1973. “National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: Hall Bridge.” May 8. Accessed March 17, 2024. https://npgallery.nps.gov/GetAsset/5f0a16c0-892f-420a-ae13-d6a8dbd4e790.

———. 1973. “National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: Worrall Bridge.” July 16. Accessed March 17, 2024. https://npgallery.nps.gov/GetAsset/5916f76e-383e-4e63-a4ad-8df9269ef692.

Hess, E.B. and Granger, A.S. 1899. Check Perforator. US Patent 621,455. Issued March 21, 1899.

Keene Evening Sentinel. 1878. “Real Estate Conveyances in Cheshire County from Mar. 14 to March 20.” Keene Evening Sentinel. March 28, 1878.

———.1900. “The West Street Bridge.” Keene Evening Sentinel. September 8, 1900.

Kingsbury, Frank Burnside. 1925. History of the Town of Surry, Cheshire County, New Hampshire: From Date of Severance from Gilsum and Westmoreland, 1769-1922, with a Genealogical Register and Map of the Town. United States.

Morse, Victor. 1960. Windham County’s famous covered bridges. Brattleboro, VT: The Book Cellar.

———. 1932. History and Genealogical Register of the Town of Langdon, Sullivan County, New Hampshire, From the Date of its severance from Walpole and Charlestown From 1787–1930. White River Junction, VT: Right Printing Co.

Newcomb, Anne. 1973a. “National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: Prentiss Bridge.” March 8. Accessed March 23, 2024. https://npgallery.nps.gov/ GetAsset/74009c04-b450-49f7-9aa2-79d34c482c1e.

———. 1973b. “National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: McDermott Bridge.” May 17. Accessed March 23, 2024. https://npgallery.nps.gov/ GetAsset/7e40d888-3f75-4b14-bb1c-57afb27d9bee.

New York Supreme Court. 1894. “N.Y. Court of Oyer and Terminer, The People of the State of New York vs. Michael J. O’Connell, Case on Appeal.”

Rutland Daily Herald. 1930. “Coffin is Ready.” Rutland Daily Herald. December 11, 1930.

Scientific American. 1899. United States: Munn & Company. March 23, 1889.

Springfield Reporter. 1941. “Gage’s Covered Bridge is 106 Years Old.” Springfield Reporter. July 25, 1941.

Strahan, Derek. 2015. Tucker Toll Bridge, Bellows Falls, Vermont. Lost New England. Accessed March 17, 2024. https://lostnewengland.com/2015/01/tucker-toll-bridge-bellows-falls-vermont-1/.

Town of Alstead. 1879, 1882. “Annual report of the town of Langdon, New Hampshire.” Langdon, NH.

Town of Langdon. 1869, 1874. “Town records, 1849–1880.” Langdon, NH.

———. 1875. “Annual report of the town of Langdon, New Hampshire.” Langdon, NH.

Transcript-Telegram. 1922. “Albert S. Granger Dead.” Transcript—Telegram, November 13, 1922, 3.

———. 1953. “Mrs. Carrie Charlton, Mother of Former Local Ford Dealer.” Transcript—Telegram, December 26, 1953, 10.

Vermont Phoenix. 1903. “Bellows Falls News.” Vermont Phoenix, July 31, 1903, 3.

Truax, Will. 2011. The Bridgewright Blog; High Water. February 26. Accessed March 17, 2024. https://bridgewright.wordpress.com/2011/10/10/high-water/.

Wagner, Scott. 2024. Interview.

Westmoreland History Committee. 1976. History of Westmoreland (Great Meadow) New Hampshire: 1741-1970, and Genealogical Data. United States: Westmoreland History Committee.