The Berry family, Jacob E. and his two sons Jacob H. and Horace W., constructed several bridges in the Mount Washington Valley between 1850 and 1885; a handful of which remain today.

The patriarch of the Berry family was Jacob Emerson Berry. He was born on September 10, 1802, in Denmark, Maine; a small town just over the state line about twenty miles east of Conway, New Hampshire. His parents were Isaac Berry (1776-1832) and Phebe Emerson (1782-1830).

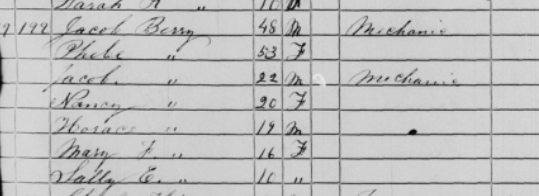

Jacob E. married a woman with his mother’s namesake, Phebe A. Merrill (1797-1872) and had five children, Jacob H. (1827-1892), Nancy R. (1829-1914), Horace W. (1831-1921), Mary F. (b. 1834), and Sally Elizabeth (1840-1911).

Jacob E. worked as a mechanic and a millwright in addition to building covered bridges. In 1850, he constructed the Saco River Bridge alongside bridge engineer Peter Paddleford (1785-1859). That same year, he constructed the frame of the Conway House, which served as one of the finest resorts in the valley until it burned in 1912.

In October 1869, one of the worst freshets in New England history caused significant damage to many covered bridges in New Hampshire and completely destroyed five.

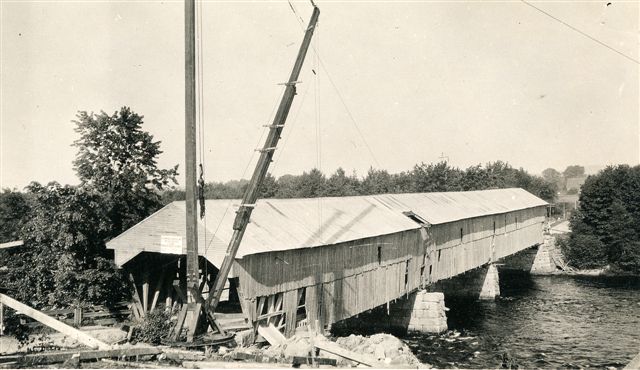

In Conway, “…the wild waters assumed such a height as to carry terror to all observers” (Merrill 1889). The raging Swift River took its namesake bridge completely off the abutments, spun it around, and sent it barreling down the Saco River, where it smashed into the Saco River Bridge, knocking that bridge loose as well. Both bridges continued their turbulent journey downstream until the intermingled pieces came to rest about a mile or two away in a giant heap of wood.

The storm was equally bad in Sandwich. “We should hardly dare tell the size of rocks that were moved or floated by the river water in the Whiteface valley; for to the skeptical people, it would seem very apocryphal” (Sandwich Historical Society 1953). Raging floodwaters not only washed the Durgin Bridge away for the third time but twisted and broke two-inch iron bolts connecting the middle pier to a large rock.

The recovery process proved to be financially rewarding for the Berrys.

The town of Sandwich also hired Jacob Berry to reconstruct the Durgin Bridge. Berry removed the center pier and raised the bridge significantly to stay at least ten feet above the flood level. Berry is rumored to have said the Durgin Bridge was built so solidly that one could fill it with wood, and it would not collapse. Whether or not anyone took him up on this is unclear but what is clear is the Durgin has remained in place since 1869.

But which Jacob Berry built the bridge, Jacob E. Berry the father, or Jacob H. Berry the son? The records are unclear.

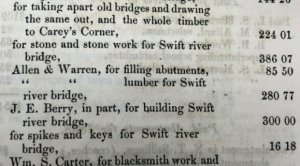

In Conway, both bridges needed to be rebuilt and interestingly, Jacob Berry was hired to reconstruct the upstream Swift River Bridge and not the Saco River Bridge that he had previously constructed. The rebuilding of the Saco River Bridge was done by Allen & Warren.

It is often reported that the Swift River Bridge was built in 1869, but it appears it was actually completed in 1870. Payments for the building of the bridge appear in town reports for 1870 and 1871, with the fiscal year ending in March, indicating the work was completed in 1870. Jacob E. was paid for partial work on the bridge in 1869.

The elder Jacob died of consumption on May 19, 1870, at the age of sixty-seven. Consumption was a term often used to describe tuberculosis, which can be a significantly debilitating disease; it is unknown how physically fit Jacob was during the construction of the Swift River Bridge and what his involvement might have been. After his death his son, Jacob H., was paid the balance due on the bridge project.

Ossipee’s Whittier Bridge, built around 1870, also has ties to the Berrys.

Ossipee residents voted at the 1870 town meeting to build a new bridge across the Bearcamp River (Bennett 2009). Henry J. Banks (1828-1873), owner of the nearby Bearcamp River House, managed the contract for the town; but who the exact builder he hired remains unclear. Many sources credit Jacob Berry (not distinguishing between Jacob E. the father or Jacob H. the son) since the bridge is similar to other Paddleford truss bridges known to have been constructed by the Berrys. Given that the elder Jacob E. Berry died in May 1870, his son, Jacob H. Berry, would be the correct person attributed. However, there are no surviving records specifying either Berry as the builder.

In 1935–36, the Carroll County Independent published two articles about the Whittier Covered Bridge construction. Both pieces featured reminiscences of four elderly gentlemen who shared their recollections of the process. Emery Moody (1851–1935) reported that Jacob H. Berry and his brother, Horace, built the bridge. Sheriff James Welch (1877–1959), who interviewed Alfonzo Mason (1857–1948), Levi Moody (1852–1938), and Charles F. Evans (1856–1946), reported that the bridge was built by “Berry and Broughton of Conway” (D. L. Ruell 1983), thus involving Charles Broughton who built covered bridges in the Conway area.

Jacob H. Berry continued to build covered bridges after his father’s death; including the 1875 Cathedral Ledge Bridge in North Conway; the 1876 Porter-Parsonfield Bridge in Maine; and the 1885 East Limington Bridge in Maine.

Jacob H. married Caroline Hurd Perkins (1833-1872) and had six children, four of whom died very young. Jacob experienced a great deal of loss in a small amount of time. Daughters Mary, age 4, and Henrietta, age 2, died of Scarlett Fever in 1859. His son Henry died at age 2 in 1868; his father died two years later. Jacob’s mother and wife died in 1872, and his two-year-old son Frank died in 1873.

Jacob worked as a millwright when he wasn’t building bridges. Jacob died on February 23, 1892, at age 64 of apoplexy.

His brother, Horace also worked as a millwright and experienced significant loss as well. In 1860, Horace married Emma Boothby (1839-1870). The couple had two daughters. Eva died at age three in 1864 and Hattie died in 1868. Emma died in January of 1870; Horace’s father would die four months later.

In 1885 at age fifty-three, Horace married Aseneth Littlefield (1858-1937). In 1906, Horace was seriously injured in a mill accident which caused him permanent physical damage. When he died at age ninety-one, Horace was the oldest man in town.

1850. Saco River Bridge. Conway. Lost in a flood 1869. Jacob E. Berry and Peter Paddleford.

1869. Durgin Bridge. Sandwich. Jacob Berry.

1870. Swift River Bridge. Conway. Jacob E. and Jacob H. Berry.

c. 1870. Whittier Bridge. Ossipee. Maybe Jacob H. Berry, not proven.

1875. Cathedral Ledge Bridge. North Conway. Removed 1951. Horace and Jacob H. Berry.

1876. Porter-Parsonfield Bridge. Parsonfield/Porter, Maine. Jacob H. Berry.

1885. East Limington Bridge. Limington/Standish, Maine. Replaced 1929. Horace and Jacob H. Berry

References

Historical photos used with permission from the Conway Historical Society, Covered Spans of Yesteryear and the National Society for the Preservation of Covered Bridges.

Bennett, Lola. 2009b. Historic American Engineering Record, Whittier Bridge, HAER No. NH-50. Washington, D.C.: National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior.

Carroll County Independent. 1936a. “Covered Bridge at Ossipee.” Carroll County Independent, March 27.

Merrill, Georgia Drew. 1889. History of Carroll County, New Hampshire. Boston, Massachusetts: W.A. Fergusson & Co.

Ruell, David L.. 1983. “National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: Whittier Bridge.” August 31. https://npgallery.nps.gov/GetAsset/77bf688a-0f06-4de1-af97-69b8f76f810b/.

Sandwich Historical Society. 1953. “Sandwich Freshets.” Thirty-Fourth Annual Excursion of the Sandwich Historical Society 7–9.

Town of Conway. 1870. “Annual report 1870. Conway, New Hampshire.” Conway, NH.

—. 1871. “Annual report 1871. Conway, New Hampshire.” Conway, NH.

Leave a Reply