“Boston” John Clark was a nineteenth-century New Hampshire builder whose work ranged from house framing and bridge construction to dam building and large-scale hydraulic engineering. Renowned for his physical strength, mechanical intuition, and unconventional intellect, he became a well-known figure in his hometown of Franklin and beyond, shaping some of the region’s most ambitious early infrastructure projects. At the same time, accounts of his life demand scrutiny, as observation, reputation, and embellishment are often tightly intertwined.

Tracing his life requires some patience with the Clark family’s naming practices. The same few given names appear repeatedly across several generations, often overlapping in time and place. This repetition can make the record difficult to follow. The nickname “Boston John,” acquired early in his working life, serves as an essential distinction and will be used here to identify the subject of this account.

Boston John’s story begins with his namesake and great-grandfather, John Clark (1680-1753), born in Haverhill, Massachusetts. This first John later removed to Stratham, New Hampshire, with his family. His son (and Boston John’s grandfather), Joseph (1719-1790), was a cooper in Stratham and eventually acquired two 200-acre lots in what was then Sanbornton: Lot No. 68, now in Tilton, and Lot No. 69, now in Franklin. Two of Joseph’s three sons would eventually settle those lands in 1775: John (1749-1832) and Captain Joseph (1752-1810).

Boston John Clark was born on one of these Sanbornton lots on October 3, 1790, to John Clark and his wife, Jane Sanborn (1765-1860). He had three siblings: Joseph (1785-1815), David (1793-1814), and Sally (1796-1866). Both of his brothers died while serving in the United States Army. Joseph died in Boston in 1815 at age thirty, and David died of camp disease in Marietta, Ohio, in 1814 at age twenty-one (Runnells 1881). It has been reported that Boston John also served in the Army, but that could not be verified.

Boston John’s nickname, often shortened to just Boston, has several origin stories.

In 1807, at age seventeen, he went to Boston and “served his time as a house builder, especially as a framer, came back at 21, and went earnestly into his trade” (Merrimack Journal 1874). Later, in the mid-1820s, he went south to work on the Boston Mill Dam, “and it was this, in connection with his learning his trade three years before, that gave him the name” (Merrimack Journal 1874). Regardless of the origin, his nickname conveniently distinguished him from the several other John Clarks living in Franklin.

Family and the Shakers

On February 3, 1814, Boston John married Elizabeth Glines (1791–1879). She was the daughter of Elizabeth Blanchard (1734–1830) and Revolutionary War veteran William Glines (1736–1830) of Northfield. The marriage took place in the Northfield home of her late brother’s widow’s second husband, Captain Thomas Clough (1740–1839), where Elizabeth was residing at the time. The couple had three children: George (1814–1900), Abraham Sanborn (1816–1835), and Albe C. (1826–1833).

Shortly after their marriage, Boston John built a house for his family and a carpenter’s shop near Cross’s Mills in what is now Franklin. They would reside there until the young family moved with the Shakers in Canterbury.

The Shakers, formally known as the United Society of Believers, were a communal religious group founded in eighteenth-century England by dissenters from Quaker and Methodist traditions. Emigrating to the United States in 1774, they established self-contained villages across the Northeast and Midwest, with Canterbury Shaker Village founded in 1792. The community combined strict discipline, celibacy, and gender separation with remarkable economic ingenuity, operating productive farms, workshops, and industries and producing goods widely respected for their quality. At its peak in the 1850s, Canterbury housed roughly 300 members on 3,000 acres, living in more than 100 buildings and maintaining a highly organized, orderly society.

During the Era of Manifestations (1837–1850), the Shakers experienced a surge of spiritual activity that included visions, ecstatic worship, and communication with spirits, reflecting broader American interest in revivalism, mesmerism, and alternative spiritual practices. Manuscripts and preserved messages document hundreds of such experiences in communities like Canterbury.

The Shakers were not alone in their fascination with spirit communication; mid-nineteenth-century America was captivated by mesmerism, or “animal magnetism,” the belief that an invisible natural force could restore health, calm the nerves, and alter consciousness. Practitioners claimed success treating chronic pain, nervous disorders, hysteria, and ailments that conventional physicians could not cure. New England proved especially fertile ground for these ideas, with lyceum lectures, traveling demonstrations, and newspaper debates bringing mesmerism into parlors, town halls, and meetinghouses. Mesmerists induced trances, performed “magnetic passes,” and sometimes exhibited subjects who appeared clairvoyant or insensible to pain, blurring the line between medical treatment and public entertainment.

Boston John’s time with the Shakers and exposure to this national fervor seemingly influenced his later career in faith healing and mesmerism. For decades, he was regarded as a mesmerist and itinerant healer, operating on the margins of conventional medicine. These experiences, combined with his extraordinary strength and skill, placed him at the intersection of religion, labor, and exploration of the unseen in nineteenth-century America.

The timeline of the Clark family’s residence at Canterbury is not entirely clear. Many published accounts state they arrived in 1835. However, Shaker records indicate that two of their sons, George and Abrahm, arrived at the Church Family on January 25, 1827; Albe was an infant and would have remained with his parents in the North Family, where the novitiate order was housed. They then left the village on May 24, 1828. The record states that when they left, “the father takes George and Abram quite contrary to their wishes” (Blinn 1891). Just over two weeks later, on June 12, fourteen-year-old George “returns to his home in the Church family, having obtained the consent of his parents. The father and mother always retained a friendly feeling toward Believers” (Blinn 1891). George remained at the Canterbury Village for the rest of his life, working as a blacksmith until his death in 1900 at age eighty-six.

The family’s later movements are similarly difficult to reconstruct. On October 13, 1833, their youngest son, Albe C., died just after his seventh birthday. Merrimack County property deeds show that Boston John, listed as John Clark IV, paid $1,600 for property along the Winnipesaukee River on November 29, 1833, from John H. Durgin. On October 30, 1834, Boston John signed a quitclaim back to Durgin. His second son, Abram, died on September 16, 1835, at age nineteen. That December, he purchased property from the widow Lydia Sanborn, which he held until he sold it to Walter Aiken in 1865. After that, “for some years they boarded at the Shakers where their son George had always remained” (Merrimack Journal 1874).

According to Boston John’s obituary, the family returned to the Shaker Village after the loss of their sons and remained there for some time. They then moved back to their former home for a year or two before building a house in Franklin. Although the precise sequence remains uncertain, Boston John maintained intermittent ties to the Shakers in various capacities for the remainder of his life.

Reputation

It has long been reported that Boston John never received any formal education; The History of Sanbornton states that he “never attended school a day in his life” (Runnels 1881), and several reports indicate that he could neither read nor write. Despite his lack of time in a classroom, Boston John showed signs of genius in measuring and framing. He was considered a man with “great mechanical genius” (Runnels 1881) and a lifelong student of hydraulic science and art.

Boston John could “carry any number, even to 100,000 feet, accurately in his head,” (Runnels 1881). Taught by his cousin, named James no less, to measure lumber with a rule, he frequently utilized a ten-foot pole to make measurements, which he did so accurately and adeptly.

An oft-repeated legend purports that while he was working in Concord, a group of troublemakers cut a couple of inches off his pole while he was eating dinner. He apparently immediately noticed and “discarded it without comment” (Granite Monthly 1922), and “never lost sight of it until the job was ended” (Granite Monthly 1895). Whether anyone dared to mess with his ten-foot pole seems unlikely given his physical description.

Physically, Boston John is described as “of stalwart frame” (Runnels 1881), at six feet two inches and 240 pounds (Runnels 1881). Stories exist of Boston John performing an earlier version of cross-fit by swinging a 700-pound roll of lead on his shoulder and walking around the lot, “as steady as a deacon” (Cross 1927). He was also reputedly unbeatable at a contest known as twisting, a test of strength in which two men grasped a bar or pole and attempted, through leverage and rotational force, to wrench it from the other’s hands. Such matches, often referred to as pole pushing or pole twisting, were common in the nineteenth century. As one account noted, “When Boston John was about, there was no betting, and the only excitement consisted in seeing how quickly he could vanquish whoever had the courage to ‘twist’ with him” (Cross 1927).

His intellect and physical strength made him a remarkable figure. “Boston John was built for a philosopher. He had a great intellect in a great body, and had his life been fashioned and environed in higher and more benign fortunes, he might have stood among the greatest philosophers or statesmen of his time” (Merrimack Journal 1874). Over the course of his career, Boston John built a wide range of structures. Still, he was most often engaged in dam building. Many accounts refer to him as a “dam builder,” a description whose double meaning may or may not have been intentional.

New Hampshire State House

One of Boston John’s major framing projects came at age 29 in the new capital city of Concord. Architect Stuart James Park (1773-1859) submitted a $32,000 proposal to build a new state house, approved by the State Legislature in 1815, with construction starting the following year. This building was constructed of New Hampshire granite, fashioned into shape by inmates from the nearby prison that Park had built a few years earlier. The Federal-style state house was designed to accommodate both legislative bodies, the governor’s offices, and public galleries, and was to be topped with a cupola adorned with a large eagle. Work began in September 1816.

Initially, Boston John was given the contract to supply lumber for the project. Reports indicate that he rafted “168,000 feet of lumber from Franklin down the Merrimack River to Concord” for the project. The timber came primarily from his farm and that of his neighbors. He was reportedly paid $5.50 per thousand feet, or $924, which would be approximately $22,000 in today’s dollars.

The trees he felled were quite large; one measured 15.5 feet in diameter at breast height and was 100 feet tall before it fell, with the top snapping off upon landing. That tree yielded a “stick of timber 85 feet long and nine inches square” (Cross 1927). His contract called for six main sills and eight timbers for the belfry. These 18-foot-long timbers were “bored through the heart, from end to end, to prevent cracking” (Cross 1927). Whilst these timbers were floating in Butler’s Eddy in Concord, another lumberman tried to lay claim to the wood. “Boston John permitted the Captain to get well along with the discussion before he pointed out to the accuser the holes in the sticks whereupon all arguments ceased” (Cross 1927).

Boston John’s involvement with the timber led to his eventual framing work on the state capital. By the summer of 1817, construction had advanced to the upper story and roof of the new State House. The framing required to carry the building’s raised central section was unusually heavy and complex, spanning the full width of what would become Representatives’ Hall and supporting the weight of the cupola above without interior posts. This work fell to Boston John.

According to The History of Merrimack and Belknap County, Park called on Boston John to frame the upper part of the building because the mechanic responsible for the lower framework “was not venturing to do the upper” (Runnels 1881). He was paid $1,600 for the job.

One of the project’s superintendents was a man named Albe Cady (1769-1843). Cady was a prominent merchant and Judge from Keene who moved to Concord in 1814. He was an abolitionist and an active member of the Episcopal Church in Concord. The relationship between Cady and Boston John is unclear, but Boston John would name his son Albe Cady Clark in 1826.

It has been reported that a man named Dudley Ladd (1789-1875) worked with Boston John to “frame and tin the dome” on the State Capitol. Ladd was reportedly a station master on the Underground Railroad, carrying escaped enslaved people through Franklin to Canada. A 2021 book about his side hustle states, “The Concord statehouse was built in 1818, and Ladd’s handiwork can be seen in the tinsmith work on the dome” (Sherburne 2021). Ladd and Clark may have tinned the original dome, but it is not the one we see today.

By the 1860s, the New Hampshire government had outgrown the two-story granite building. Architect Gridley J.F. Bryant (1816-1899) designed a larger building, incorporating the existing structure while adding a new third floor and a larger gold dome on the top. The 1819 cupola was replaced entirely. As Boston John was in his mid-seventies by then, it is unlikely that he participated in the project. The claims that he built the gold dome on today’s state house are more than likely false.

Dams and Hydraulic Engineering

Boston John’s dam-building career began in 1818 and was successful in part due to his assistant, Enos F. Brown (1796-1881) of Bridgewater. Brown was known as “Boston John’s Diving Bell,” because he could reportedly dive deeper and remain underwater longer than any man. “He would go 15 or 20 feet under water and knock around with his hammer as if in the air,” (Clark 1927).

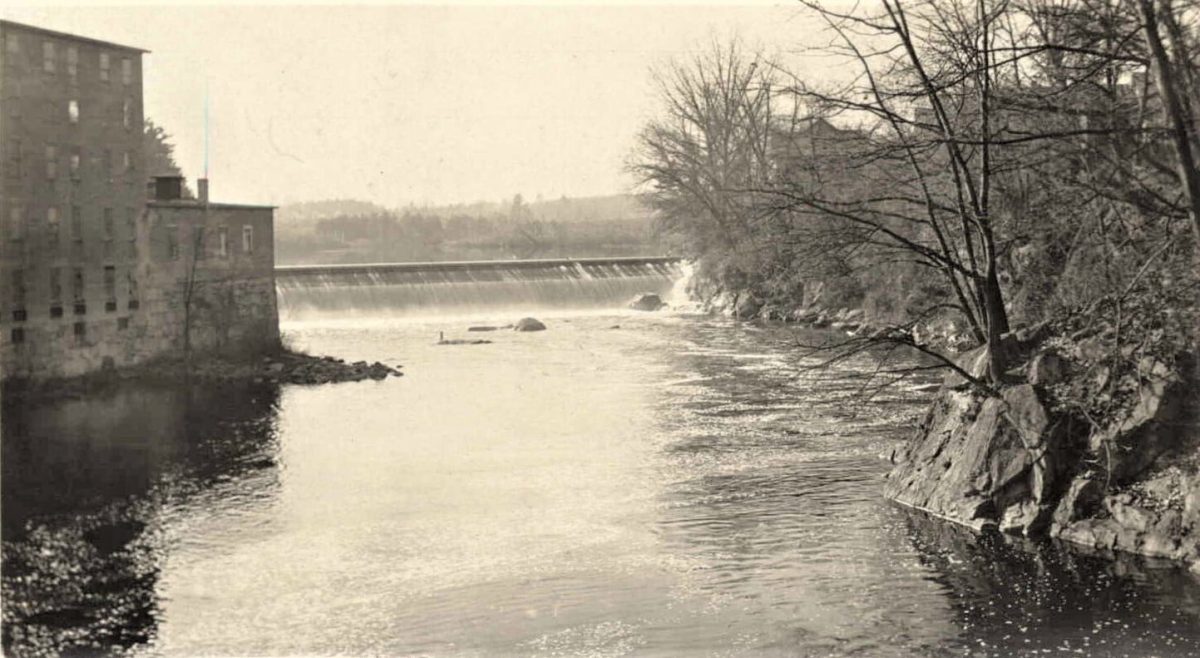

In 1818, Boston John built a dam near Bow Street in Franklin by Robinson’s machine shop and Walter Aiken’s finishing room. He was paid $300. By 1864, Aiken built a large mill complex on the site that later became Stevens Mill. Boston John also reportedly built the Amsden Dam at Fisherville (now Penacook), near what became the H.H. Amsden Furniture Company, and the dam at Bristol over the Pemigewasset River. Details on those two dams have not yet been located.

Following completion of the state house project, Stuart Park relocated to Boston to work on one of the country’s largest dams. The Boston Mill Dam (officially the Boston & Roxbury Mill Dam) was an early 19th-century engineering project built between 1818 and 1821 to dam Boston’s Back Bay tidal basin to harness tidal water power for industrial mills and create a raised roadway (now Beacon Street) connecting Boston to its western neighbors. The venture proved a commercial failure; few mills were built, costs far exceeded estimates, and stagnant water contributed to sanitation issues, yet the dam laid the foundation for later land reclamation that produced today’s Back Bay neighborhood.

Boston John reportedly worked on this project, perhaps remembered by Stuart Park, and was asked to participate. The History of Sanbornton reports that he was “called to Boston to superintend the erection of a tide-water dam” (Runnels 1881) in 1823. But the Boston Dam was done and opened by 1821. However, an article in the Pittsfield Sun from January 1823 states that the Boston and Roxbury Mill Dam Corporation sought to widen their dam (Pittsfield Sun 1823). No records about the Boston and Roxbury Mill Dam list Boston John as a superintendent, but it is possible he worked on the project.

He was, however, hired in 1833 by the Proprietors of the Sewall’s Falls Locks and Canal to build a canal from Sewall’s Falls to the mouth of Mill Brook in Concord. He and his crews had dug about half of the two-and-a-half-mile canal when the corporation abandoned the project. The dam would eventually be built in 1894.

Boston John reportedly worked on another dam in Lawrence, Massachusetts. The Great Stone Dam was an unprecedented 900-foot masonry gravity dam built on the Merrimack River at Bodwell’s Falls between 1845 and 1848 to raise the river head and power textile mills as part of the Essex Company’s plan to create Lawrence, Massachusetts. At the time of its construction, it was the largest dam in the world.

His obituary states that Boston John was the “chief supervisor in all the hydraulic works on the Winnipiseogee lake and river, when the Lake Company was putting down the foundations of its improvements a third of a century ago, there was no man to be found anywhere, in those days of his mature experience and full intellectual strength, who could so easily as he, and so surely conquer an ugly spot of water power. He grasped the situation at a glance, the work fashioned in his own way and which he pronounced solid, was never known to move” (Merrimack Journal 1874).

Bridges and Transportation

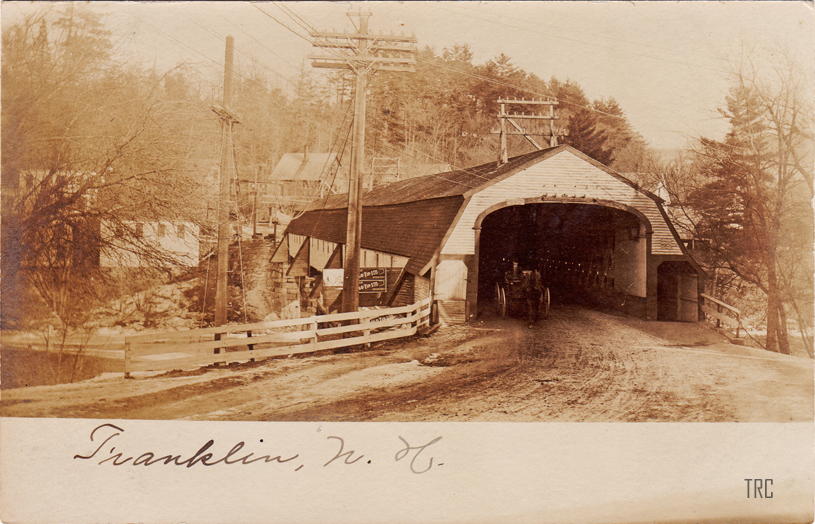

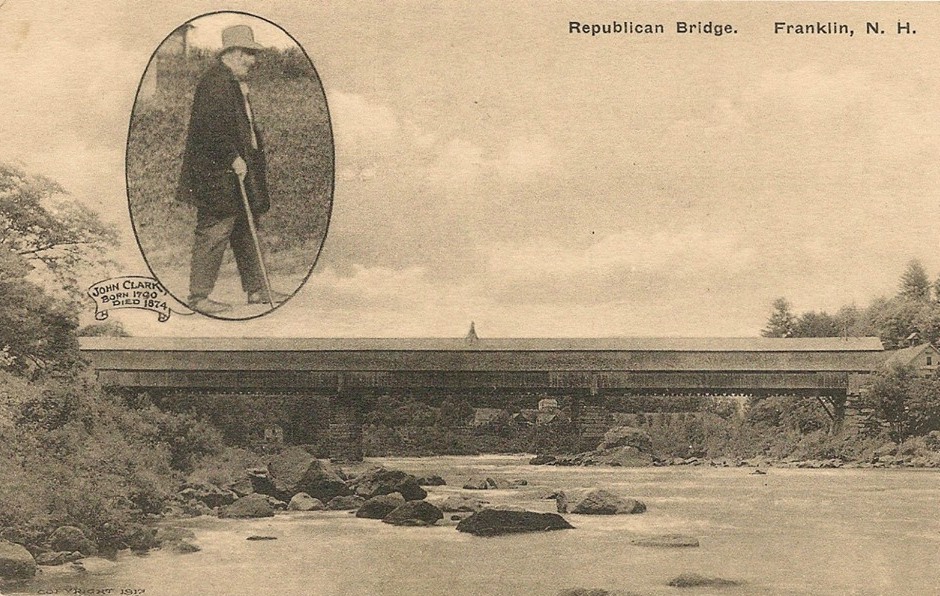

Franklin’s nickname, Three Rivers City, certainly implies that bridges will be needed to get from here to there. The first bridge to be built over the Pemigewasset River was built in 1802 and was named the Republican Bridge, “reflecting a chief phase of political excitement of the time” (Runnels 1881). That bridge was replaced in 1824 and stood until a powerful storm destroyed it and the nearby Federal Bridge on Sunday, January 27, 1839.

The City of Franklin hired Boston John to build its replacement. The Republican Bridge was a 400-foot-long, three-span, Town lattice truss bridge that cost $7,000. The structure had a covered pedestrian walkway on each side and was one of only two covered bridges in New England with a gambrel roof. Boston John spent the summer building this unique toll bridge connecting Franklin to Franklin Falls. The trunnels, wooden pegs used to hold the pieces of wood together, were made of white oak and delivered in six ox cart trips by Herrick Aiken (1797-1866). The stone abutments were constructed by John Ladd (1807-1873) with granite hauled by Stephen Kenrick (1806-1884).

The bridge collected tolls on the west side of the river until 1845. In June 1879, the bridge was damaged by a freshet. The abutments were repaired using granite from Stuart Park’s recently demolished State prison in Concord. The Republican Bridge was dismantled in 1931 and replaced with the Daniel Webster Bridge. The timber was used for other purposes, and the granite stones were laid as riprap along the riverbank. The New Hampshire Historical Society has a gavel made from the timber, and the Franklin Historical Society has a display case full of items made from the discarded wood.

In 1840, Boston John built a new water wheel for the tannery at Canterbury Shaker Village.

In 1845, the Northern Railroad enlisted the help of Boston John to construct trestles over the Merrimack River to extend the railroad from Concord to Franklin. Instead, he “informed the officials that it would be cheaper to change the course of the river… thus came about the famous Boston John cutouts of the Merrimack River” (Cross 1927). He used oxen to excavate channels that widened and deepened the river, thereby straightening it. The soil he removed was used to supplement the railroad beds.

In 1848, Boston John was involved in the construction of another bridge, but it differed significantly from his Republican Bridge. The Enfield Shakers sought a more direct route to the new railroad station in North Enfield, rather than the five-mile trip around Mascoma Lake. They hired George W. Fifield (1806–1867) as project superintendent and Boston John to design a bridge to span the lake. Because the site spanned water more than 40 feet deep with an additional 30 feet of mud, conventional bridge construction was impractical, and the structure was conceived as more of a causeway than a bridge.

Built of logs, stone, and earth atop pilings, the Shaker Bridge was considered the only bridge of its kind at the time. The bridge opened in 1849 and remained in service until it was destroyed by the 1938 hurricane. “Most early travelers were afraid of crossing the Shaker Bridge because of the roller coaster effect combined with its zigzag motion” (Beale 2002). It was often called the “famous Shaker Bridge” and a “wonder of all who view it” (Colby 1907).

An article in the Enfield Advocate from 1904 states that Boston John was “the engineer and overseer of the whole work” (Cumings 1904). However, a later news account includes a letter from Fifield’s daughter indicating that Boston John was present for “a week to advise, but I believe it was well underway before he came” (Newspaper 1907).

Mesmerist

Boston John Clark’s reputation as a mesmerist reportedly brought him into the orbit of Mary Baker Eddy (1821–1910), founder of the Christian Science movement. In the 1840s, before her later prominence, she was simply Mary Baker, daughter of the strict and often volatile Mark Baker of Sanbornton Bridge (now Tilton). Mary Baker experienced recurring periods of illness throughout her youth and early adulthood, episodes later described by contemporaries as sudden and dramatic. Seeking relief, she eventually turned to mesmerist Phineas Parkhurst Quimby (1802-1866), whose influence she later acknowledged as formative. The religious meaning she drew from these experiences would culminate decades later in the founding of Christian Science.

In a biographical series published in McClure’s magazine, Georgine Milmine (c.1871-1950) claimed that Mark Baker (1785-1865) summoned Boston John Clark to the family home in Sanbornton during the 1840s in an attempt to cure his daughter. This assertion is disputed. Writing in Human Life magazine in 1907, author Sibyl Wilbur (1871-1946) concluded that Eddy and Clark likely never met.

A separate anecdote comes from Franklin native Sarah Clement (1833-1913), who recalled a drowning of seminary students in the Winnipesaukee River. Clement stated that a man known as “Boston John” sought to hypnotize Mary Baker to locate a missing body, believing her to be a receptive subject. According to Clement, Mary accurately predicted the body’s location—an outcome Clement attributed to common sense rather than clairvoyance (McNeil 2017).

This account was flatly rejected by Caroline A. Rowell (1836-1916) in an affidavit dated January 10, 1907. Rowell stated that she had “never heard of [Mary Baker Eddy] being in any way associated with Boston John Clark as a pupil or even interested in mesmerism or spiritualism,” adding that she would have known had such an association existed (McNeil 2017).

Regardless of his brush with fame, his wife was not too keen on his powers. In an 1838 letter on file at the Western Reserve Historical Society, David Parker wrote, “Perhaps you may remember of having heard of one John Clarke of Franklin, NH, who attended meeting the first Sabbath we were at New Lebanon last. He is a great mill wright & his only son George is in the Church at Canterbury. Br. Rufus, Elder Richard, & Samuel Swett know him. That meeting had a very powerful effect upon him. He talks much of the supernatural power he there witnessed & has, we learn, said he must set out. The world now, some of them, call him Shaker. It is also said he has offered his wife who has no faith $1000 if she would separate from him” (Parker 1838).

One man whom Boston John used his powers of hypnosis on was Jeremiah Fisher Daniell (1800–1868), owner of the J. F. Daniell & Son mill. Daniell severely damaged his arm when it got caught in some machinery, and he was experiencing extreme pain and sleeplessness. One visit from Boston John put Daniell into a deep sleep, allowing his wound to heal. He reportedly healed others in town of severe headaches with “a few magic passes of his hands” (McNeil 2017).

Pastor Wilton E. Cross’s report on Boston John claims he was quite the prankster. “One citizen of Franklin, in particular, was a constant victim, for at the sight of the influence of Boston John would cause this man to go through all the motions incident upon the sawing of wood” (Cross 1927). Another tale recounts, “a scene which never failed to strike awe to its beholders was Boston John on the street drawing a circle with his cane about some urchin and telling him he couldn’t get out of the circle” (Cross 1927). These tales are accompanied by another that claims Boston John, after chiding four men who couldn’t move a large log, tied a rooster to the log, “and at the signal ‘go’ the little red rooster went hopping along dragging the huge log behind” (Cross 1927). Clearly, his legend became greatly exaggerated over time.

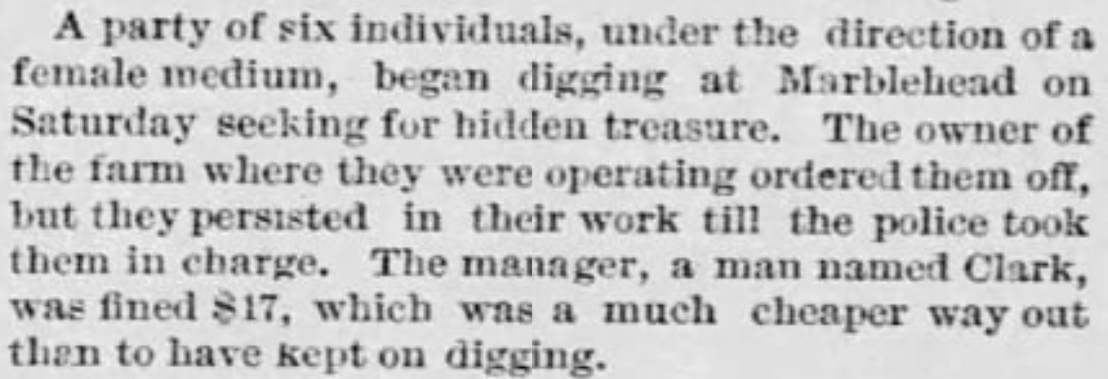

Boston John’s powers eventually got him into a bit of trouble. After communing with the spirits to seek the location of Captain Kidd’s long-lost treasure in Marblehead, Massachusetts, he and a small group of people left Franklin to dig for buried treasure. In 1872, he and five others, including a female medium, were fined $17 for digging a hole on a Sparhawk farm in Naugus Head in search of buried treasure. An article in the Boston Globe on July 31, 1872, reports, “the owner of the farm where they were operating ordered them off, but they persisted in their work till the police took them in charge. The manager, a man named Clark, was fined $17, which was a much cheaper way out then to have kept on digging” (Boston Globe 1872).

Final Years

Boston John was known to partake in a different kind of spirits as well. One story tells of him attempting to cross the Winnipesaukee River on the ice with a jug of “the old familiar juice” under his arm. When the thin ice broke beneath his large frame, “all those who beheld the accident could make out was the old high beaver hat bobbing up and down” (Cross 1927), but noticed that before he fell, Boston John “stretched forth his arm and deposited [the jug] as far as possible from the water” (Cross 1927).

Another tale recounts a local man overtaking Boston John walking home after a night of drinking. When the man offered Boston John a ride, indicating that his walk home was a long one, he replied, “It’s not the length of the way that bothers me, it’s the width” (Cross 1927).

In 1861, Boston John “came near making a last plunge over one of his dams” (McFarland 1899). The seventy-one-year-old was crossing the mill pond above Aiken dam on the ice on a track cleared by previous travelers. Soon enough, all 240 pounds of him fell through the ice. A man named Henry Crane intervened. Boston John reportedly shouted to him, “Bring me a long board,” and “forthwith, Boston and his cane were standing erect again, unharmed saved a gentle chill, which he says was at once dispelled by warm and soothing drinks,” (McFarland 1899).

It has long been reported that Boston John resided with the Shakers in Enfield at the end of his life. However, he was, in fact, in Canterbury.

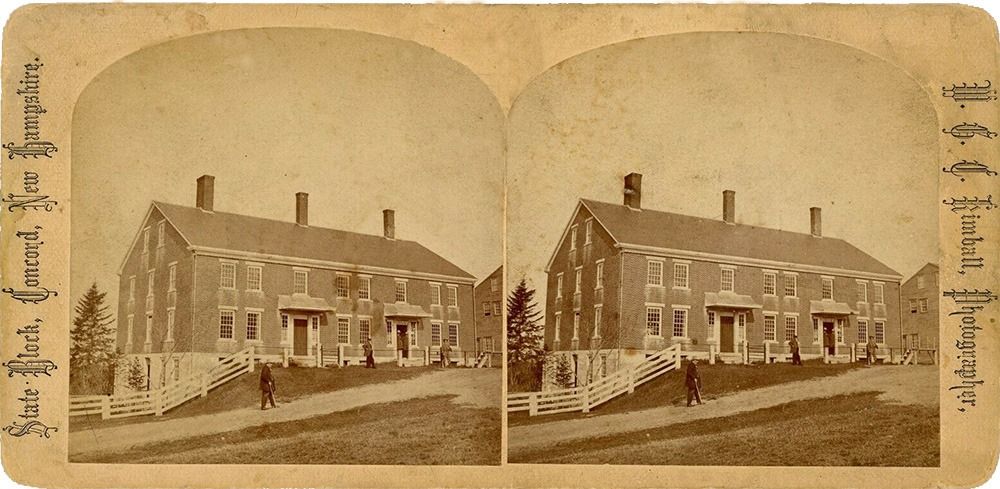

A single photo of Boston John exists, cropped from a larger image of a Shaker building and taken by photographer W. G. E. Kimball of Concord. After careful inspection, the photo is determined to depict the Church Family Trustees’ Building at Canterbury. One can see Boston John walking with his cane in front of the building in Canterbury, not Enfield.

Boston John died of dropsy on October 30, 1874, at the age of 82. His obituary states, “Boston John is dead. His stalwart form … will be seen no more. He was 84 years old and for half a century was a famous man all up and down the country from the Green Mountains to the Nutmeg State” (Merrimack Journal 1874). Several reports indicate that Boston John “died with the Shakers,” but he in fact died at the same family home he was married in, as he and his wife had been boarding there with her great nephew, Jonathan Scribner (1813-1888). His body was, however, prepared for burial by two Canterbury Shaker Sisters, Sally Ceeley (1805-1898) and Abby M. Hall (b. 1831), before his internment in the Franklin Falls Cemetery.

Stories followed Boston John Clark during his life and long after it. Some can be supported by the record; others cannot. He had no formal engineering training, yet he built dams and bridges that endured. He understood timber, stone, and water, working from experience rather than theory. Over time, fact and legend blurred, but his work remains a steady point of reference—quiet, practical, and lasting.

References

Historical photos are a part of the author’s collection or were used with permission from the New Hampshire Historical Society, Ruth Speed, Penacook Historical Society, and Todd Clark, National Society for the Preservation of Covered Bridges.

Special thanks to Michael O’Connor and Mary Ann Haagen, Enfield Shaker Museum; Shirley Wajda, Canterbury Shaker Village; and Leigh Webb, Franklin Historical Society.

Beale, Galen. 2002. “The Shaker Bridge.” The Friends’ Quarterly, XIV, no. 3 (Summer 2002).

Blinn, Henry Clay. 1891. “A Historical Record of the Society of Believers in Canterbury, N.H., From the time of its organization in 1792 Till the year one thousand, eight hundred and forty eight,” 1891 (Ms. #763, Canterbury Shaker Village Archives, transcription).

__. c. 1895. “Church Record by Henry Clay Blinn,” c. 1895 (Ms. #764, Canterbury Shaker Village Archives, transcription).

City of Franklin. 1930. Annual Report of the City of Franklin. Franklin, NH: City of Franklin.

Colby, Edith Mellish. 1907. “Shakers in Enfield.” The Granite Monthly: A Magazine of Literature, History and State Progress, 1907.

Concord Monitor. 2024. “Vintage Views: The Simple Genius – John Clark.” Concord Monitor, 2024.

Cross, Lucy Rogers Hill. 1905. History of Northfield, New Hampshire 1780–1905: In Two Parts with Many Biographical Sketches and Portraits Also Pictures of Public Buildings and Private Residences. Rumford, ME: Rumford Printing Company.

Cross, Wilton E. 1927. “‘Boston John’ Clark, Master Builder.” New Hampshire State Library. Transcribed with corrections in The Official History of Franklin, New Hampshire, vol. 1, by Albert G. Garneau, 2002. Franklin, NH: Albert G. Garneau.

Cumings, Henry. 1904. “Building of Shaker Bridge.” Enfield Advocate. Transcribed by Enfield Shaker Museum, December 2, 1904.

“[John Clark].” 1838. August 27, 1838. CSV #764, p. 122. Transcription by Enfield Shaker Museum, Enfield, NH.

Garneau, Albert G. 2002. The Official History of Franklin, New Hampshire, vol. I. Franklin, NH: Albert G. Garneau.

Garvin, James L., and Donna-Belle Garvin. 2018. “The Granite State House.” Historical New Hampshire 71, no. 2 (Fall/Winter 2018).

Granite Monthly. 1922. “‘Boston John’ Clark: A Picturesque Figure in Franklin History.” Granite Monthly: New Hampshire State Magazine, vol. LIV, 1922.

Hadley, Amos, and Will B. Howe. 1903. History of Concord, New Hampshire. Concord, NH: Rumford Press.

Hamilton College Manuscript. “Current Records of Events from 1792 to 1885: Record in brief of the accession of members, and Building of the Church at Canterbury, N.H,” Transcribed by the Canterbury Shaker Village.

Hurd, D. Hamilton. 1885. History of Merrimack and Belknap Counties, New Hampshire. Philadelphia, PA: J. W. Lewis & Company.

Leighton, Fred. 1910. “The Evolution of the New Hampshire State House.” The Granite Monthly: A Magazine of Literature, History and State Progress, 1910.

Means, Andrew. 1978. “Builder Toted a Measure of Franklin’s Past.” Concord Monitor, August 2, 1978.

Merrimack Journal. 1874. “Boston John Clark.” Merrimack Journal, November 6, 1874. Transcribed by Enfield Shaker Museum.

McFarland, Henry. 1899. Sixty Years in Concord and Elsewhere: Personal Recollections. Concord, NH.

McNeil, Keith. 2017. A Story Untold: A History of the Quimby–Eddy Debate. https://ppquimby-mbeddydebate.com/about/. Retrieved January 18, 2026.

Moses, George H. 1895. “New Hampshire’s Youngest City: A Sketch of Franklin.” Granite Monthly: New Hampshire State Magazine, vol. XVIII, 1895.

New England Ski Museum. 1989. New Hampshire, A Guide to the Granite State. United States.

New Hampshire Historical Society. 2026. “Sewall’s Falls Dam, 1892 October 8.” New Hampshire Historical Society Collections. https://www.nhhistory.org/object/936852/sewall-s-falls-dam-1892-october-8. Retrieved January 18, 2026.

Newspaper Clipping. 1907. Transcribed by Enfield Shaker Museum, September 13, 1907.

Parker, David. 1838. “Letter from Enfield, New Hampshire, to Seth Y. Wells, August 27, 1838.” WRHS Manuscripts, IV A 4. Transcription by Enfield Shaker Museum, Enfield, NH.

Pittsfield Sun. 1823. Pittsfield Sun, January 23, 1823, 3.

Runnels, Moses Thurston. 1881. History of Sanbornton, New Hampshire. Boston: A. Mudge & Son, printers.

Shaker Manuscript Records. 2026. Shared with the author by Enfield Shaker Museum.

Sherburne, Michelle Arnosky. 2021. Slavery & the Underground Railroad in New Hampshire. United States: Arcadia Publishing.

Sherman, Carrie, and John W. Hession. 2019. “The People’s House for Two Centuries.” New Hampshire Home, April 15, 2019.

Spain, James W., II. 2024. “The Simple Genius.” Concord Monitor, May 4, 2024.

Starbuck, David R. n.d. “Historic American Engineering Record, Sewall’s Falls Hydroelectric Facility, HAER No. NH-20.” Washington, D.C.: National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior.

Leave a Reply