John Clark Briggs was born in Putney, Vermont, on May 28, 1824. Briggs was the last of five children born to Silas S. Briggs (1788-1864) and his wife, Lucy Davidson (1789-1866). Their first child, Silas (1814-1815), died at only fifteen months old. Their only daughter, Lucy Philena (1816-1840), was born in Plymouth, Vermont, and their son, Silas Parmenas (1817-1886), was born in Ludlow, Vermont. The birthplace of younger sons Joseph Davidson (1818-1878) and John Clark is not known but is frequently cited as Vermont.

In the early nineteenth century, the family moved eighty miles west to Saratoga, New York, where they lived on a five-acre farm. The elder Silas supported the family as an insurance agent and ensured that his sons were educated. The details of Briggs’ high school education are unclear, but we know he attended Burr Seminary alongside his brother, Joseph, in 1835.

Brothers Silas and Joseph would go on to study law together at the University of Vermont from 1839-1841. Silas transferred to Union College, where he would graduate in 1843. The two worked as practicing attorneys for the remainder of their careers.

John Briggs followed his older brother to Union College but chose an engineering career instead, graduating in 1845 with a degree in civil engineering. In 1849, Silas married Sarah Stickney (1826-1890) and moved to her hometown of Calais, Maine, to practice law. Twenty-six-year-old Briggs went with them. By 1850, he lived with his brother and sister-in-law and worked as a teacher. But the Briggs didn’t stay in Calais long, and while Silas and Sarah moved back to Saratoga, Briggs found himself in the middle of New Hampshire.

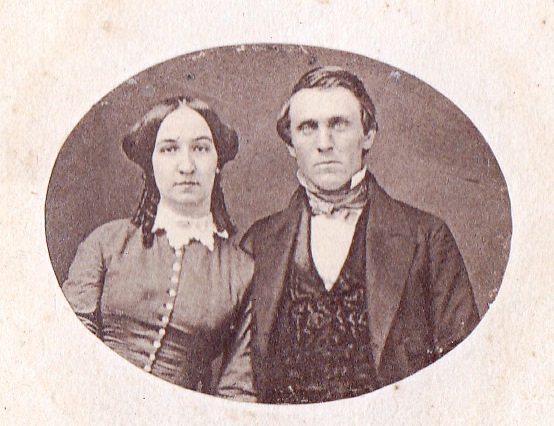

On December 14, 1853, Briggs purchased property on the corner of Washington and High Streets in Concord. The next day, he married Lucy Hatch Chase of Hillsboro, New Hampshire. Lucy was born in 1832 to James Chase (1786-1884) and Lucinda Andrews (1794-1884). Where the couple met is unclear, but after their marriage, they would make their home twenty miles east of Hillsboro in the capital city.

In 1855, Briggs received patent No. 13,451 for a conical pendulum clock. His unique design features a rotating steel ball pendulum suspended from a string at the front of the face. The ball is driven by a spring movement underneath the piece. The components are enclosed in a glass dome and sit on cast iron paw feet. According to the patent, “by this arrangement, the operation of the clock is noiseless. It does not tick. There is no reciprocating motion” (Briggs 1855).

Known as the Mystery, Briggs Rotary, or Flying Ball clock, the clocks were made by the E.N. Welch Manufacturing Co. of Bristol, Connecticut, through the 1870s. Vintage Briggs Rotary Clocks are still collectibles and are available online.

Briggs was active in the Concord community and served as president of the Ward 4 Common Council. He was also a member of the Republican party. Briggs was the chief marshal of a grand parade in Concord as part of the 1856 presidential campaign. The procession, “went over…the principal streets, and then counter-marched in alternate lines in State House Park until the square was full to overflowing, beside thousands of men to spare” (Lyford, Hadley & Howe 1903).

On April 4, 1857, Briggs and his wife welcomed their only child, a daughter named Emma Josephine.

In November 1858, Briggs was awarded a second patent, not for clocks but for bridges. Patent No. 22,106 was for the invention of a “new and improved mode of giving elasticity to the compressed joints of truss frames,” and reads, “The invention consists in the application of springs to the bearings of either the posts, main braces, counter braces, iron rods of all descriptions, or to any compressed joint in trusses constructed either of wood, iron, or wood and iron combined. The most convenient and available material for these springs is India rubber… short solid cylinders, with holes through their centers” (Briggs 1858).

In 1859, Briggs was appointed by the Concord City Council to develop a new cemetery. Thirty acres of land was purchased on North State Street for $4,500 with the plan to create a municipal cemetery in the then-popular rural style. Designed much like a public park, these cemeteries were a departure from the traditional burial grounds of the time. Rural cemeteries included natural features, roads and paths, and elaborate memorials for the dead.

Briggs, “whose eminent ability as a civil engineer,” and “was fully equaled by his skills and taste as a landscape gardener,” (Lyford, Hadley & Howe 1903), was appointed to design the layout of the new burial ground. Blossom Hill Cemetery opened in 1860 with 170 lots laid out. The cemetery features two grand entrances, winding roads, a running stream, and grassy paths. The first burials were up on the hill, where visitors had commanding views of the city.

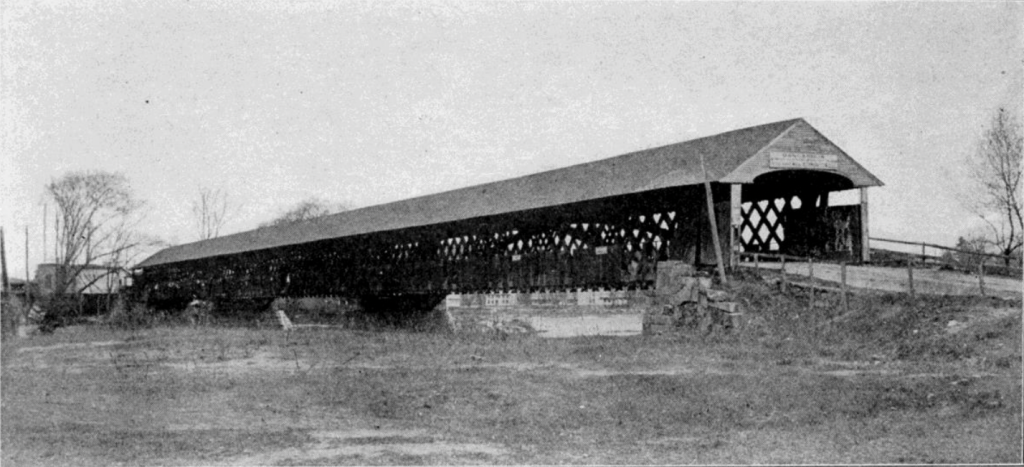

That same year, Briggs was hired by the town of Hooksett to rebuild the Village Bridge that had been destroyed by an ice flow in March. Town reports indicate the cost of the bridge project was a hefty $9,916.37, $3.3 million in today’s dollars. Briggs was paid a total of $5,200. It is assumed that he built the timber superstructure, but unfortunately, the records do not specify his specific role in the project.

The 1860 Census lists John and Lucy Briggs living in Concord with their three-year-old daughter, Emma Josephine, and an eighteen-year-old domestic helper named Harriet E. Hook. Property deeds indicate that Briggs purchased a home at the intersection of Spring, Cambridge, and Academy Streets in 1860. His civil engineering business was a few houses down the block on the corner of Washington and Spring Streets in a property he purchased in 1857. But a little over a year later, Lucy died on February 10, 1861, at age 30. A cause of death cannot be found.

Briggs buried his young wife in the cemetery he designed. The Briggs’ large square plot rests high up on the hill and is bordered with granite stones. Large, old cedar trees stand at three corners of the plot; in the fourth corner, only remnants of a tree remain. The small headstone is enclosed in a tent-like granite structure featuring four short granite pillars topped with a square granite roof. Briggs’ memorial to his wife is unlike any other at Blossom Hill: a beautiful tribute to a woman gone too soon.

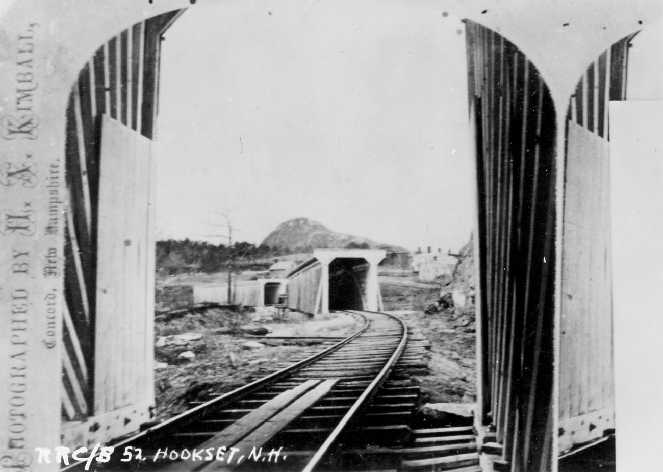

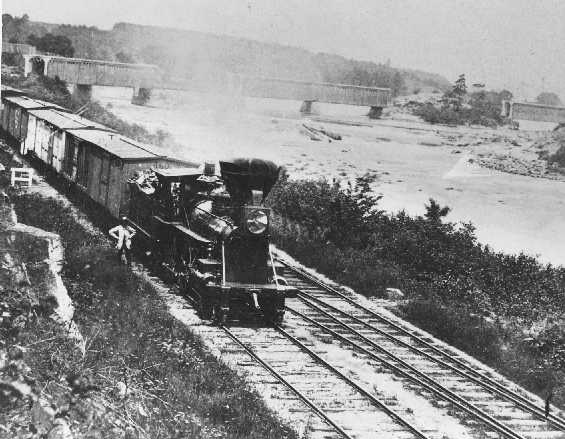

In 1861, a truss design created by Briggs was employed in three covered railroad bridges in Hooksett. Briggs would receive patent No. 38,653 in 1863, but he had been advertising his truss variant for some time prior. His timber lattice truss configuration became known as the Briggs Triple Lattice Truss. The patent reads, “This improvement consists in stiffening the truss by the crossing of inclined ties, combined with inclined braces, with an additional stepping piece above the sills at each end to bolt the braces into, and an end brace or post mortised to the underside of the upper sill and projected laterally to a secure step on the foundation” (Briggs 1863).

Constructed by Cole & Company of Lake Village (later Laconia) and designed by Briggs, the Triple Bridges at Hooksett carried the railroad over the Merrimack River. One two-span 175′ bridge connected to an island in the river. The railroad continued past the island and to the shore over a three-span, 308′ bridge and a two-span, 186′ bridge. All three bridges stood for seven years before being damaged by a flood in 1888.

In 1862, Briggs constructed the Henniker Road Bridge in nearby West Hopkinton. This single-span, 164’ bridge employed his triple lattice truss design and crossed the Contoocook River along a new road to Henniker. The new road and bridge project cost $1,978.43; Briggs was paid $1,450 “in part for bridge” (Town of Henniker 1862). The Henniker Road Bridge was replaced in 1936.

Also that year, Briggs was hired by the City of Concord to rebuild the Sewall’s Falls Bridge. The first bridge at this location over the Merrimack River was constructed in 1835 and lost in an ice jam in 1839. That bridge was replaced in 1840, only to be destroyed during a log drive nine years later. A covered wooden truss bridge was constructed in 1853 by Philip Henry Paddleford at this location. It lasted until January 1, 1862, when it was destroyed by a “gale of wind.” That year, the City of Concord hired Briggs to build yet another bridge. This 300’ structure consisted of “long arches of wood reaching from pier to abutments, with a deck or roadway on top, without covering to protect it from the weather” (City of Concord 1875). He was paid $566.47. Briggs’ structure was reportedly covered three years later and stood for close to a decade before being destroyed by a log jam in 1872. No photos exist of this iteration of the Sewall’s Falls Bridge.

Beginning in 1854, several local communities employed Briggs for engineering, surveying, and bridge repair work, but that seems to have ended in 1863. In June of that year, Briggs registered for the Civil War Draft in Concord but was not called into service. Little information about Briggs is recorded for the next two years, likely due to an illness that cut his career, and his life, short.

On May 26, 1865, Briggs died of consumption at his family’s home in Saratoga. He was two days shy of his 41st birthday.

Consumption, later identified as tuberculosis, killed more people in New England in the nineteenth century than any other disease. The physical effects were debilitating, causing a literal wasting-away, or consumption, of the patient. Those who made it through their first bout would suffer debilitating recurrences for the rest of their lives. It is not known when Briggs began his struggle with consumption and how long he suffered. Perhaps it took the life of his wife three years before him. We may never know.

At age 8, Emma Josephine Briggs was left an orphan. She went to live with her grandmother, Lucy, and her uncle, Joseph, in Saratoga. Lucy died the following year. In her will, Lucy identifies that Emma Josephine had “no general guardian” and appoints John S. Thurber as a “special guardian.” Where Emma Josephine went after the death of her grandmother is unknown.

In 1878, Josephine married New Hampshire attorney Butler Amzi “B.A.” Jones (1848-1922). In 1880, the couple lived in Indiantown, Illinois, with a son named Harry. The 1900 census shows the family living in Sidney, Nebraska, and indicates the couple had had six children, with only two surviving. By 1920, the couple had relocated to Portland, Oregon. Josephine died there in 1931.

John C. Briggs’ impact here in New Hampshire was brief but significant. Despite his contributions to bridge design and clock making, he is best remembered for the cemetery he created on the hill. After his death, Briggs’ brothers returned to Concord to settle his affairs and to bury him beside his wife. His epitaph is carved on the backside of Lucy’s marble stone and humbly reads, “first surveyor of this cemetery.” Today, the Briggs’ lay at rest, enclosed in granite and shaded by 160-year-old cedars, high on the hill in the city they called home for their brief lives.

References

Historical photos were used with permission from Covered Spans of Yesteryear and the National Society for the Preservation of Covered Bridges.

Special thanks to Pete Mori, Concord City Clerk’s Office; Joe Lueck, Outreach & Reference Archivist, Union College; Dave Anderson, Society for the Protection of New Hampshire Forests; LaRae Rutenbar, John C. Briggs’ great-granddaughter.

Briggs, John C. 1859. Application of the Conical Pendulum to Timekeepers. US Patent 13,451, issued August 21, 1855.

Briggs, John C. 1858. Truss Bridge. US Patent 22,106, issued November 23, 1858.

Briggs, John C. 1863. Improvement in Bridges. US Patent 38,653, issued May 26, 1863.

Browne, George Waldo. 1921. The History of Hillsborough, New Hampshire, 1735-1921. United States: John B. Clarke Company.

Casella, Richard M. 2016. Hooksett Village Bridge. Portsmouth, RI: Historic Documentation Company, Inc.

City of Concord. 1854, 1855, 1857, 1858, 1860, 1861, 1862, 1863, 1875. “Annual report of the city of Concord, New Hampshire.” Concord, NH.

Hannibal, Edna Anne. 1969. Clement Briggs of Plymouth Colony and his Descendants, 1621-1965. United States.

Journal of the Franklin Institute. 1856. United States: Elsevier.

Knowlton, Rev. I.C. 1875. Annals of Calais, Maine. United States: J.A. Sears, Printer.

Lyford, James Otis, Hadley, Amos, Howe, Will B. 1903. History of Concord, New Hampshire: From the Original Grant in Seventeen Hundred and Twenty-five to the Opening of the Twentieth Century. United States: Rumford Press.

Town of Henniker. 1860, 1861, 1862. “Annual report of the town of Henniker, New Hampshire.” Henniker, NH.

Town of Hooksett. 1860, 1861. “Annual report of the town of Hooksett, New Hampshire.” Hooksett, NH.

Town of Hopkinton. 1862. “Annual report of the town of Hopkinton, New Hampshire.” Hopkinton, NH.

Truax, Will. 2014. The Bridgewright Blog. December 31. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://bridgewright.wordpress.com/tag/triple-lattice/.