Prior to researching covered bridges, I spent a good amount of time researching genealogy. I’ve traced my Varney ancestors from New Durham and Dover to the West Indies and the Salem Witch Trials, all the way back to 12th-century England. I’ve traced my husband’s Chandler line to John Chandler, who arrived at Jamestown Island as an unaccompanied nine-year-old in 1609. I’ve found quite a few exciting things on this journey, including that King Henry III of England is my 22nd great-grandfather. But no matter where the rabbit hole leads, the research starts with the same essential baseline questions for each person – name, date of birth, and place of birth.

I approached my covered bridge research in quite the same manner. I began each covered bridge narrative with four essential questions – when it was built, where it was built, how much it cost, and who built it. For most of New Hampshire’s covered bridges, I was able to answer all four of these basic questions before Covered Bridges of New Hampshire went to print. But others remained unanswered and left gaping holes in my stories.

I don’t care for loose ends.

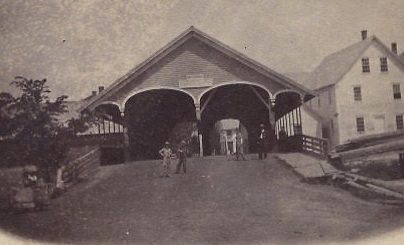

Such was the story of Lancaster’s Mechanic Street Bridge.

We know the bridge was built in 1862. Local merchant Richard P. Kent (1806–1885) kept a diary in which he documented the construction of the new Mechanic Street Bridge. Kent noted that construction commenced on June 11, 1862. He noted that the first team crossed the covered bridge on Tuesday, November 18, 1862.

We know it was at least the second bridge across the Israel River at this location. Kent wrote that the covered bridge replaced an unsafe wooden bridge. Mechanic Street was laid out in 1852, and by 1859 the road was extended through “Mr. Joyslin’s land for the continuation of the street leading from the Town Hall to the house of Gilman Colby. We learn that the bridge is commenced” as reported in the Coos Republican (Bennett 2004).” This led some to infer the covered bridge was built in 1859, but it was not, thanks to Mr. Kent.

We know that the town of Lancaster constructed both the Mechanic Street Bridge and the Main Street/Double Barrel Bridge in 1862 and that both bridges cost $2,610 to construct. The town sadly lumped the expenses for both bridges into one line item in their town report. Even more sad is that the Main Street/Double Barrel Bridge was damaged beyond repair in 1886 and subsequently replaced.

What we haven’t known for 161 years is who built the bridge. It seems neither the town nor Mr. Kent found this detail important enough to write down.

It’s been a bone of contention for decades. At the Mechanic Street Bridge’s 100th birthday celebration, the Coos Republican reported, “It is fortunate that Mr. Kent cared enough to have jotted down these two items, for the town report for the year 1862 failed to even mention the bridge, let alone the cost of building or the builder.”

During my initial visit to research in Lancaster in 2021, I met with Barbara Robarts of the Weeks Memorial Library. In addition to providing me with historical documents about Lancaster’s covered bridges, she told me there were seven boxes of unsorted town receipts marked “roads and bridges.” In the short time that I had to spend there, I sorted through one box and found several promising receipts from 1862. But I didn’t have time to go through them all.

Finally, this February, I made the trip back.

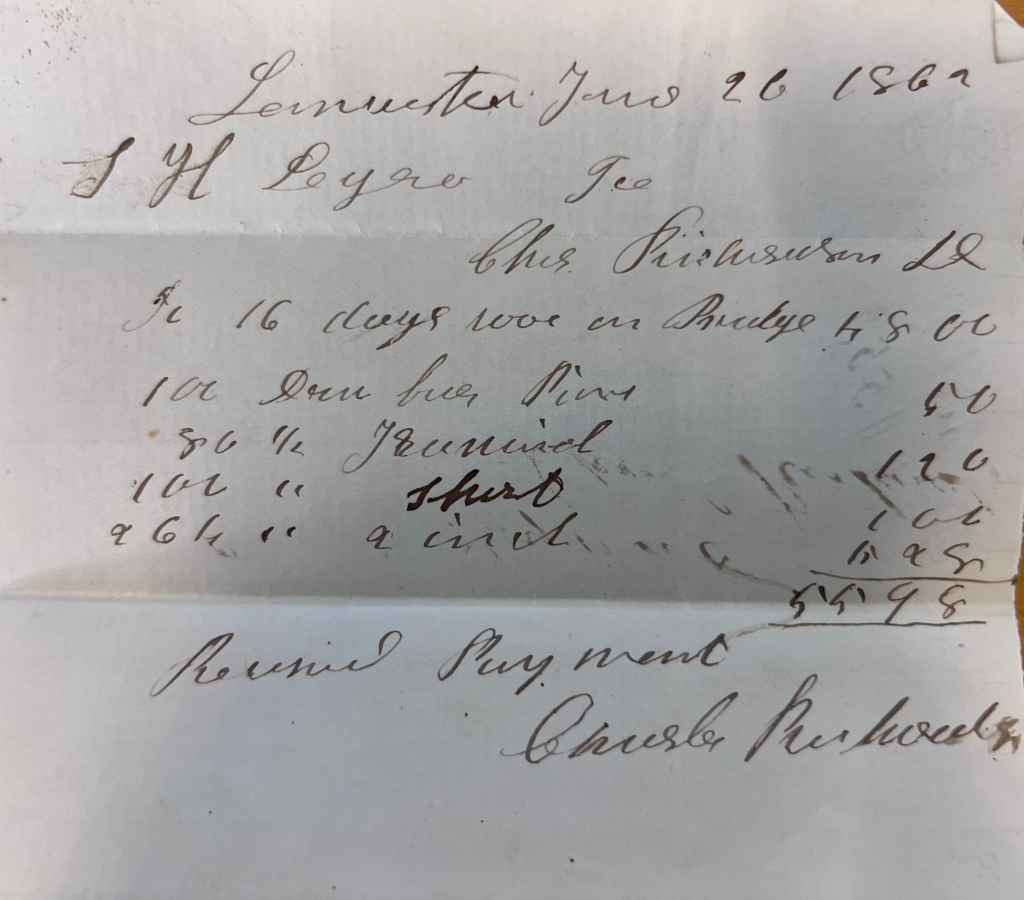

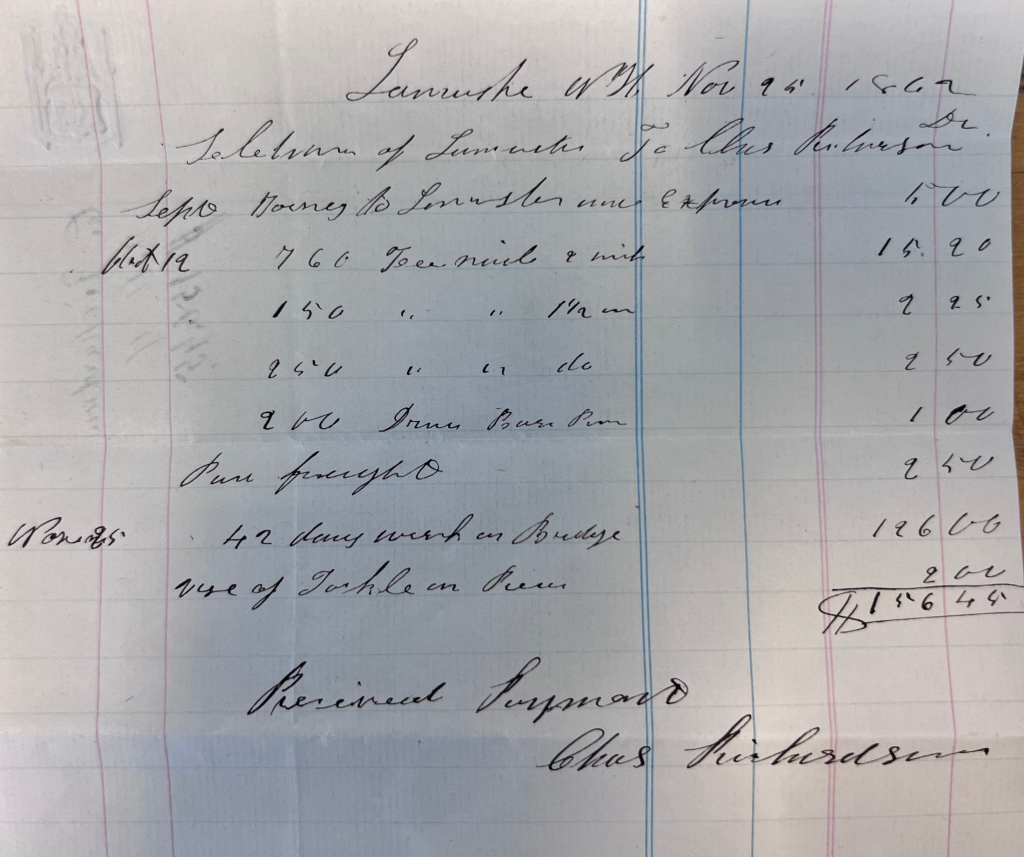

Barbara graciously gave my husband and me seven boxes of handwritten receipts from the 1800s. For over three hours, we reviewed hundreds of small pieces of paper, some official receipts from a pre-printed book and others literally torn from a full sheet. Each receipt was handwritten with an ink-well pen in cursive script, some legible, some not so much. We pulled out any receipt mentioning bridge work in 1862 and piled them on the table. Finally, in the last box, we hit paydirt.

Charles Richardson built the Mechanic Street Bridge.

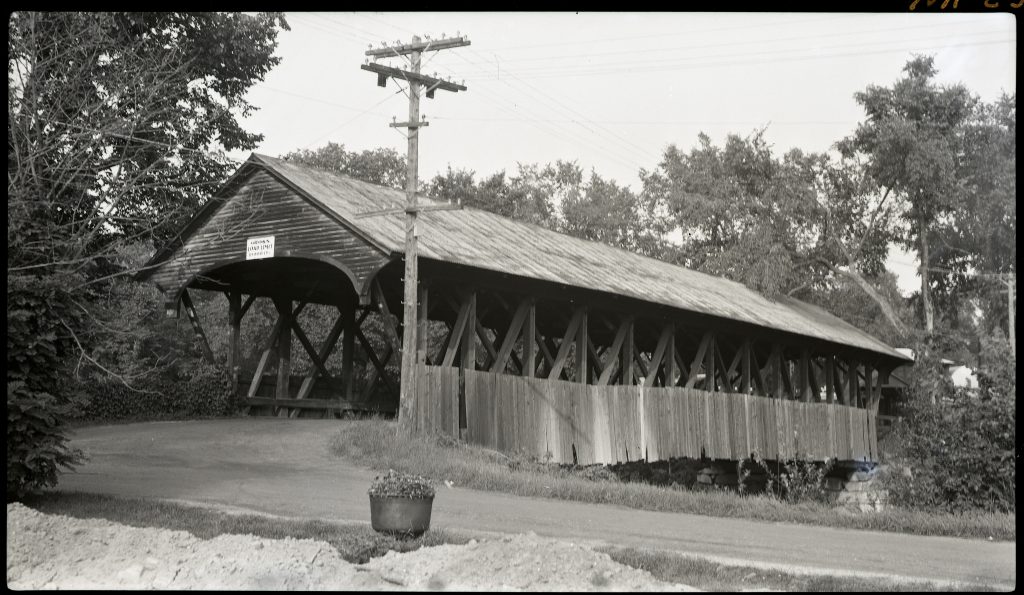

It comes as little surprise that Charles Richardson had a hand in building the two Lancaster covered bridges. Ten years earlier, “Charles Richardson and Son” were credited for building the Groveton Bridge ten miles up the road. The elder Richardson was also rumored to have built the Stark Bridge in 1857. The four bridges are very similar in design; it would be a safe bet that the same person constructed them. Just take a look for yourself.

So who was Charles Richardson? Well, there were two.

Captain Charles Richardson (1806–1894) was the son of John Richardson (1758–1823) and Sarah Wilder (1764–1851). Richardson married Unity Partridge (1814–1836) and had his first son, Charles P. (1836–1906). Unity died six weeks after her son was born. Richardson then married Miranda Cook (1815– 1897) and had seven more children, four of whom were sons.

In addition to owning a farm, Richardson operated Charles Richardson & Co. lumber manufacturing in Northumberland. He worked as a furniture and chair maker in addition to constructing covered bridges. The 1870 and 1880 censuses both report his occupation as a bridge builder. Richardson built the Guildhall-Northumberland Bridge in 1855. He is often called “Captain,” but his military service is still unclear. Richardson died of heart failure at the age of eighty-eight in 1894.

Richardson “and son” built the Groveton Bridge in 1852 when he was 46 years old. So who was the “son?” His oldest son Charles P. was sixteen years old at the time. Two of Richardson’s younger sons died within a week of each other in 1851; the remaining two were under the age of eight in 1852. Therefore, Charles P. should be credited with helping his father construct the Groveton Bridge.

Young Charles’s career trajectory seems to reinforce this theory. Vital records indicate that the younger Charles followed in his father’s footsteps. His occupation is listed as a carpenter (1857), carpenter journeyman (1860), mechanic (1860), millwright (1880), building mover (1900), and millwright (1905).

Given the elder Charles’ definitive occupation as a bridge builder, it may be safe to assume that he was the builder of both the Main Street Bridge and the Mechanic Street Bridge. Perhaps his son worked alongside him. Either way, one or both of them were involved.

The receipts we culled totaled $2,558.94, $51.06 short of the amount expensed in 1862. We either missed some receipts, or they aren’t in the box, but I’m rather pleased with the proximity. The payments for both covered bridges began in May 1862 and ended in November and simply refer to work on “the bridge.” An analysis of the receipts indicates that the abutments were constructed by Samuel Davidson (1805-1878). Davidson was paid a total of $705 over six installments. Timber was purchased from farmer Emmons S. Freeman (1833-1924), farmer William F. Smith (1820-1896), Anson F. Weston, C.B. Allen & Co, and carpenter William L. Rowell (1835-1917).

Other men who were paid to work on the bridges include merchant William H. Heath (1824-1889), mason Daniel W. Spaulding (1826–1881), carpenter Joseph Nutter (1829–1890), farmer Edward Melcher (1825–1897), David Young (b. 1819), Richard O. Young (1842–1862) who was killed in the Civil War shortly after working on the bridge, carpenter Seneca B. Congdon (1822–1912), farmer James Legro (1826–1909), laborer Freeman S. Moulton (1837–1907), carpenter Frank B. Smith (1832–1909), mason Chester C. Fisk, laborer Daniel W. Spaulding (1814-1883), Fielding Smith, farmer Francis Kellum (1833-1896), George Smith, Daniel Pellum, Richard M. J. Grant (b.1836), George T. Wentworth (1842-1913), Nelson B. Lindsey, road agent Samuel H. Legro (b. 1825), farmer Samuel S. McDonald (b.1823), and someone identified as O. Nutter.

Charles Richardson was first paid for nineteen days of work on May 21, 1862. On June 26, he was paid for 16 days. Since Kent’s diary states work on the Mechanic Street Bridge began on June 11, we can assume the bulk of these days were for the Main Street Bridge. Richardson was subsequently paid for expenses such as board, belts, pine, nails, treenails, freight, and use of tackle. On November 9, he was paid for “42 days work on the bridge,” bringing his total to seventy-seven work days for both bridges. In all, he was paid $328.49.

One loose end is tied up; now, on to the next.

Did Charles Richardson build the Stark bridge, and if so, when? It is unclear exactly when the current bridge was constructed and by whom, but the town has settled on 1862. The Union Church was built in 1853, and the bridge is often attributed to being constructed at this time; some publications claim 1857 as the date. An article by Muriel Rogers Stuart (1913–1990) in the July 1947 edition of New Hampshire Highways Magazine credits Captain Richardson as the builder and unilaterally states it was built in 1857, but this has not been corroborated (Stuart 1947). Stuart served as an auditor for the town of Stark, and her husband, Raymond, served on the school board and as town moderator. It is unclear if she had documented information or was reciting oral tradition.

I intend to find out.

References

Historical photos were used with permission from Anne Morgan, Covered Spans of Yesteryear, and the National Society for the Preservation of Covered Bridges.

Bennett, Lola. 2004. Historic American Engineering Record, Mechanic StreetBridge, HAER No. NH-45. Washington, D.C.: National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior.

Stuart, Muriel V. Rogers. 1947. “Stark Covered Bridge.” New Hampshire Highways Magazine, July.